A few more things about the farmers' strike, or as Página/12 calls it, the agricultural businessmen's lockout. The strike, lockout, or whatever you call it, is now on hold while the leaders of the movement wait for their call to negotiate with the government.

Covers of Página/12 and La Nación for March 26 (the day after Cristina's inflammatory first speech, the cacerolazos in upper-class Buenos Aires, and the disbanding of Plaza de Mayo demonstrators by Luis D'Elía's thugs).

Covers of Página/12 and La Nación for March 26 (the day after Cristina's inflammatory first speech, the cacerolazos in upper-class Buenos Aires, and the disbanding of Plaza de Mayo demonstrators by Luis D'Elía's thugs).

Since the subject of

Página/12's word choice came up, here's something I meant to say before. I was appalled by

Página's coverage of the conflict. I'm well aware that

Página is a leftist newspaper, and like all media, they select news and editorialize on them from that perspective. I'm a lefty myself, not a radical, but in general I'm in agreement with that perspective.

Sometimes

Página's op-eds go over the top and I don't like that; I don't like how certain people in their staff see 1970s' politics, or class struggle, or whatever their pet subject, in every bit of current news. To balance that, I read

La Nación, which is right-wing and anti-government, but also has a few really good writers, alongside some whose opinions make my stomach turn.

Well, my discovery these days was that

Página/12 is obviously, visibly, on the pay of the national government.

Página's coverage of the strike/lockout was so deliberately skewed, so unctuously pro-government, so grossly anti-strike, so monolithically defensive of Cristina, that I can't be convinced that ideology alone is responsible. I felt angry. The rest of the media coverage was sloppy, partial, sensationalist, sentimental..., as usual. Even

La Nación didn't dig so much in the trash.

Página's was a pro-government campaign, almost as subtle as Luis D'Elía screaming his hate for the rich.

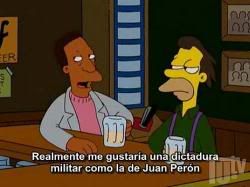

The fact is, I'm a "salad bar"-type political pragmatist. I tend to distrust and discount the opinions of people who are in the extremes, but outside of those, I applaud anyone, from the left or the right, who comes up with a good idea, or something that looks like a good idea. I had a deep distrust of Néstor Kirchner when he ran for president. I changed my mind as he did some really cool things, like renewing the Supreme Court, facing up to the utility companies that wanted to triple their fees, maneuvering around the defaulted bond-holders who would see the country broke to get paid, and repealing the laws that prevented the torturers and murderers of the last dictatorship from being tried. Then he started channeling Juan Domingo Perón or something (that is, Perón minus the articulateness and good diction in speeches) and the worst elements in his government acquired power, and then he passed it all on to Cristina, who has been doing exactly the opposite of what should be done since Day 1.

All this time (getting back to the subject) I heard Néstor and Cristina criticizing the media for this and that. Néstor K once said the media should inform objectively instead of doing opposition politics (that is, kill the editorial section, kill political analysis — just repeat whatever the government officially communicates to the press), and more than once he pointed at specific journalists and specific papers. Cristina is even worse. For all her supposed communicational talents, she sounded remarkably stupid, to me at least, when she tried to make a sarcastic comment — "It seems as if the media were forbidden from printing good news." The Kirchners never understood journalism, maybe because in Santa Cruz the media were few and were controlled by their friends and cronies.

Up to the export tax crisis,

Página/12 was (so it seemed to me) rather neutral, not in the sense that it didn't editorialize, but in the sense that it wasn't systematically putting out an apology of the government.

La Nación, on the other hand (so it seemed to me) was always trying to poke holes in everything the government did. Granted, as of late

Página would have real trouble finding something good to say about the government, and the ideological strain was showing; and

La Nación was enjoying a free ride on the scandal rollercoaster, so it came out as more objective (negative spin wasn't necessary) and didn't look so clearly anti-government.

When the countryside rose,

Página/12 suddenly shifted gears (or so it seemed to me...) and launched an all-out offensive against the critics of the Kirchner administration. Even the witty Rudy & Paz comics became bitter, unfunny attacks on the "oligarchy". You could count a half-dozen headlines each day, every one of them a long editorial piece, pointing out the many sins, past and present, of the participants in the protest — and not one objective criticism of the idiotic measure taken by the Ministry of Economy which had caused all the trouble in the first place.

It got me really mad. I've gone mad with

La Nación over the coverage of certain episodes by specific writers, here and there, and I'm accustomed to see through its supposed objectivity into its rotten conservative heart. But I didn't expect this from

Página: a whole paper, which used to cover a variety of topics seriously when appropriate, or with well-placed irony and sarcasm in other cases, turned overnight into a government propaganda machine. Not for a left-wing government, but for an administration that's fast turning us back to old-style fascism. I can barely read it anymore. In fact, since the

campo crisis started, I almost don't read about it in the papers — I pick and choose only the shorter informative articles, and quickly skip over the editorials.

It's all bare ideology out there now. Dialogue, compromise and solutions seem to have been banished.

There's an outrage here over the 10th episode of the 19th season of

There's an outrage here over the 10th episode of the 19th season of

Now that the farmers are off the roads and the president is off her soapbox (the farmers are hastily harvesting; the president is busy in Paris — see, I can even alliterate parenthetically!) I'll say some things I've been holding up about this mess we've all gotten into.

Now that the farmers are off the roads and the president is off her soapbox (the farmers are hastily harvesting; the president is busy in Paris — see, I can even alliterate parenthetically!) I'll say some things I've been holding up about this mess we've all gotten into.

La Pampilla was just a spot along the road. We'd somehow gotten the idea that there were huge signs pointing to where the adventurous tourist was supposed to go, but no. We almost climbed over a fence on the wrong side of the road, until we spotted a sign and a path on the opposite side. We took it. It was cold (10 degrees? 5 degrees?) and there was a drizzle, and wind blowing it into our faces (I had to take off my glasses). About a mile later, shivering and dripping wet, we came to the park rangers' house. We were informed of the various dangers (including pumas) and sent on our way, with the warning that there weren't any other human-built shelters of any kind beyond that point. Yipee.

La Pampilla was just a spot along the road. We'd somehow gotten the idea that there were huge signs pointing to where the adventurous tourist was supposed to go, but no. We almost climbed over a fence on the wrong side of the road, until we spotted a sign and a path on the opposite side. We took it. It was cold (10 degrees? 5 degrees?) and there was a drizzle, and wind blowing it into our faces (I had to take off my glasses). About a mile later, shivering and dripping wet, we came to the park rangers' house. We were informed of the various dangers (including pumas) and sent on our way, with the warning that there weren't any other human-built shelters of any kind beyond that point. Yipee. Soon we stopped feeling so cold. The landscape was soberly beautiful and the road wasn't steep. However, we were literally inside a rain cloud most of the time. By the time we reached the middle point, we were soaked all over, except where our windbreakers had (partially) protected us. We forged on. We got to the last marked spot (number 10), and there we found a sign indicating the way for the place where you could actually see the condors... 45 minutes away.

Soon we stopped feeling so cold. The landscape was soberly beautiful and the road wasn't steep. However, we were literally inside a rain cloud most of the time. By the time we reached the middle point, we were soaked all over, except where our windbreakers had (partially) protected us. We forged on. We got to the last marked spot (number 10), and there we found a sign indicating the way for the place where you could actually see the condors... 45 minutes away.