I haven't written about the influenza A(H1N1) epidemic in Argentina. Everyone else has, though, so I'll leave it at that. For me, it had its good and bad sides. The good side was that children and teenagers cleared the streets, buses, and other public venues for us grownups, leaving us room to enjoy our city without being bumped into, or bombarded with trashy music out of MP3 players. Oh, some people died. Not many, certainly an insignificant number compared to the people who die of other preventable diseases or in traffic accidents caused by drivers' carelessness. Several acquaintances of mine fell with the flu, but it was nothing serious.

The bad side was the hysteria and the paranoia. I'm sure you've seen your share of this. What happens here is that as soon as, let's say, an outbreak of a disease is announced, society divides itself into two main groups: those who panic, go to ridiculous extremes to protect themselves, and generally bother the rest of us, and those who just dismiss it all as an invention of the government, the media, or both to make us forget of the really important matters, and place the rest of us at risk because of their carelessness. You may have noticed there's a third group, what I've called "the rest of us" — make of that what you want.

As the first wave of the flu subsided, many people have started to forget the cautionary measures against contagion. This may or may not be OK. Others continue to be hysterical, in both the usual and the figurative meaning: they remain fearful and paranoid, and they're very funny — tending towards the "pathetic" kind of funny. At work, I've had perfectly healthy people, who usually offered me their cheek to kiss every morning, refuse to come even close to me. During the initial phase of the epidemic, one of my co-workers first became very agitated, then tried to force her daughter's school to shut down, and then basically locked her up at home (this was a few days before the Ministry of Education finally decided to shut down the schools). There's still alcohol gel everywhere, and by the looks of it, some people think it's an all-powerful, virus-proof barrier against the flu.

The cold, and with it the flu, will be gone in less than two months. I can't wait to tell you about the upcoming dengue epidemic...

03 August 2009

The flu

30 June 2009

After the elections

The legislative elections are over, and if you're following the news, you'll be surely aware of the big picture: Néstor Kirchner has lost, the government's power in Congress has been cut down, and several presidenciables (that is, likely presidential candidates) are already lining up (or have been lined up by the media) for the 2011 election.

So I'll just concentrate on the small things and the analysis. First, let's get Kirchner out of the way... Néstor Kirchner lost to Francisco de Narváez by a handful of votes, a lot of votes actually, but only about two-and-a-half percent of the Buenos Aires Province vote. Of course, what happened is that the list of candidates headed by NK got a few votes less than that led by FDN; in formal terms it was a tie, but Kirchner's insistence on the paramount importance of this election worked like a self-fulfilled prophecy: almost everyone assumed positions as if it were the one and final battle of a war, and the election turned into an opportunity to bash the government. And bashed it was: Kirchner, who had achieved record levels of popularity during his term, lost to a group of the strangest bedfellows politics has inflicted on us as of late, led by a right-wing Colombian-born multimillionaire with an image constructed hastily by the media in a matter of months. Many of the so-called "barons" of Greater Buenos Aires, who rule the poorest and most densely populated parts of Argentina as virtual feudal lords and are keen observers of reality, betrayed their alliance with Kirchner, unnanounced.

In any case, after what must have been a very long night and a terrible day, Kirchner dutifully resigned from the presidency of the Justicialist Party. He released a short video accepting the defeat and I swear he looked mildly drugged.

Yesterday in the afternoon, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner gave a press conference. First she started out by reciting highly optimistic figures for the composition of the new Congress, and feigned not to have the exact numbers of her husband's defeat on hand (while, as everyone knows, she probably had the figures down to the least significant digit painfully etched in her short-term memory). Then she tried to turn the whole thing on its head, pointing out how an awful lot of people had still voted for the government's party. When a journalist pointed out that she'd gotten 45% of the vote when she was elected and now her husband got only 31%, she was upset and accused the media of having a double standard because they hadn't gone and asked that to Mauricio Macri and his candidate Gabriela Michetti (in the City of Buenos Aires, Michetti got 30% of the vote, only half of what Macri and her had gotten two years ago). She also resented the petitio principii of a journalist who asked about the manipulation of INDEC's figures of inflation — which did beg the question, of course, because the government has never admitted to that manipulation, although everyone, including some of the president's favorite economists, is certain of it.

At that point, approximately, I stopped watching the press conference. It was pointless. Either Cristina has learned nothing or she needs a few days to let it sink in, but based on previous experience, the latter is unlikely. We're left with the hope that she won't attempt something funny before December, when the new Congressmen will take their seats.

26 June 2009

Before the elections (II)

I left out some details in my previous post about the upcoming legislative election, just to keep it short and avoid digression. I think I need to clarify some things, for those who don't live in Argentina and have no idea what's the voting system is like. Some general information can be found in the Wikipedia articles Elections in Argentina and Argentine legislative election, 2009, but here I'm interested in the little things that make fraud and deceitful tactics easy (or easier).

There are two kinds of problems with this election (and many past ones): what I'd call ethical problems, and systemic problems. The latter are technical details; the former are often allowed (or encouraged) by the latter. Let me explain.

The main systemic problem in legislative elections is the fact that, for Deputies (the members of the Lower House), we use proportional representation, whereby you vote for party-approved lists of candidates, rather than single candidates. The more votes a list receives, the more candidates the party gets elected. This in itself is not bad, but in a very uninformed society like Argentina's, it means most people don't know who they're voting for, beyond the first candidate in the list, who's usually chosen to be as charismatic and well-known a character as possible. Most of our current representatives never have to do any campaigning besides standing next to the "poster guy", and get elected merely because they've secured (by whatever means) a place in the list.

Compounding this, there's another problem with the system: we use paper ballots as a universal means of vote, and each party or coalition is in charge of printing and supplying the public with their ballots. When you go to vote, you're let into a cuarto oscuro (literally, a "dark room", though of course it's not dark) where you face dozens of piles of ballots, each with different logos, party symbols, colors, etc. The ballots for each party have the party name and the first candidate in the list printed in large type; the second and maybe the third and fourth candidates in the list are printed somewhat smaller, and the rest are in normal type. There's nothing to stop the sensible, concerned citizen from reading and assessing the whole list, but as I said, Argentina's political culture is very primitive, so most people only know the first candidate and will vote for him or her without paying attention to the rest of the bandwagon, or simply look for the party name among the ballots and put that into the envelope.

The different ballots thing also enables a whole host of fraudulent activities. For example, pseudo-parties created with the sole purpose of having an extra ballot in the "dark room" and confuse the voters, either by closely mimicking the name and typography chosen by another party, or by suggesting there are alternatives where there aren't (in this case the pseudo-party might be a "mirror" of another party — different name, same candidates). There are (in)famous cases of parties registered only to have a first candidate with a last name very similar to a major candidate of another party.

The state must pay for the ballots so each party has an opportunity to participate even if it doesn't have a lot of contributors. In every election, many little parties pop into existence, ask the state for money to print their ballots, and vanish. Control is absent.

If the ballots for a party run out, they have to be replenished by the delegates of the party present in the election table. If the party couldn't provide a delegate, the ballots won't be replenished and some people might have to go without voting for the party they had in mind. So it's a very common practice in some areas for voters to be sent into the voting rooms to steal or ruin other party's ballots. People can be also sent in to plant fake ballots for a competing party, differring from the real ones by minor details that won't be noticed by the voters, but will be cause for voiding them afterwards, during the count.

It's quite clear these problems exist and could be easily solved by printing a single standard ballot, with the names of all the candidates in it, and having the voters mark them with a pen, as is done in other countries. It's also very clear why this hasn't been done — the party that most benefits from these tactics is the one in power, and wishes to remain so.

Some other problems with the system derive from the fact that the laws regulating the elections are lax, and moreover, nobody respects them, and the judges are unable or unwilling to do anything about it. But mostly the remaining problem is one of ethics. There's no law forbidding a person from running as candidate to a post he or she will never accept once elected (or will accept only to resign immediately), but in a normal society such dishonest behavior would be punished by public opinion; in Argentina, however, we have "testimonial candidates" at the top of the public's preferences.

The main offender in the ethics field is, no doubt, the Front for Victory, i.e. Kirchnerism. As is regrettably usual in Argentine politics, but taken to the extreme by the ruling couple and their allies, there's a confusion and merging of the conceptual limits of state, government and party. One sees Néstor Kirchner campaigning and can almost forget he's only a candidate in a given district — the full structure of the national government has been put at his disposal (funds, transportation, official coverage, the Cabinet, the President herself), even though it's illegal (and even more so because it's just before an election). We have no president, we have a ruling cabal presided by Néstor Kirchner, and Congress is virtually non-existent.

There are many who still passionately support the Kirchners because of their past achievements regarding human rights, the renewel of the Supreme Court, and the economic recovery, as well as the idea (unfounded in my opinion) that their ethical "rough edges" will be polished in time. Despite the fact that wealth inequality hasn't decreased and that the Kirchners show no sign of changing their friends' capitalism for socialism, many in the left still believe "the model" is an ongoing revolution towards a better country. Others don't have that faith, but refuse to position themselves against the Kirchners because they know the opposition is worse.

Despite all the problems with our system, I still hope we can all change this state of affairs. Right now the battle between Kirchnerism and opposition is a zero-sum game. Maybe after next Sunday, or next year (once the candidates have taken office) the politicians who haven't done anything but fight each other will find a way to discuss and, if necessary, compromise, so we can move on.

Labels: 2009 elections, argentina, argentine politics, election, politics

04 May 2009

Marijuana March 2009 in Rosario

Last Saturday it was the tenth edition of the Global Marijuana March, and Rosario wouldn't be left out of it, so an event for the legalization of the private use of cannabis was scheduled. Yours truly hasn't even had a tobacco cigarette in his life, but I do support the right of people to smoke whatever they want provided they don't hurt anyone else, so I attended just to see what it was all about.

Last Saturday it was the tenth edition of the Global Marijuana March, and Rosario wouldn't be left out of it, so an event for the legalization of the private use of cannabis was scheduled. Yours truly hasn't even had a tobacco cigarette in his life, but I do support the right of people to smoke whatever they want provided they don't hurt anyone else, so I attended just to see what it was all about.

The meeting place was the spot beside the Planetarium, within the Parque Urquiza, and the time was 3 PM. Marisa and I had a very late lunch, and we couldn't make it until after 4 PM. I had my doubts, because it was supposedly a march, i.e. people would not stay there just waiting for us to come. But there was no march, only fairly scattered groups sitting in the park. Some activists had mounted stands and were giving out pamphlets explaining what marijuana is, the kind of care you must take if you're going to smoke it or eat it, etc.; others asked for the legalization of cultivation for private use and for government-sponsored strategies of damage reduction. A guy walked around disguised as the cannabis plant, in a green foam rubber suit, and people took pictures of themselves with him.

It was sunny and warm, a typical day for this weird autumn. Like ourselves, many had brought thermos and mate, while of course more than a few others were smoking joints. It was all rather calm, with people coming and leaving all the time, while joggers ran and elderly couples strolled by the site, probably curious but not seemingly alarmed. We stayed until our mate ran out, then left for a walk down the coast.

Anything to do with cannabis is illegal in Argentina, which seems rather stupid. As in many other places, the victims are the consumers: if they're caught, they're subject to all-too-frequent police abuse, and if they become addicted, they get treated like criminals. Lots of people sell, buy and smoke marijuana in bars and discos, and the law against it only serves to set up a bribe system benefitting the police and the authorities. Of course, the ones who make money selling bad-quality drugs to the poor are elsewhere.

Banning the possession of marijuana for private use has been deemed unconstitutional several times (per Article 19 of the Constitution, such things are "exempt from the authority of magistrates"). The Supreme Court is currently withholding its position, but it seems the majority wants the repressive law to be repealed.

27 January 2009

Up it goes

Everything goes up and stays there these days, especially taxes and the heat.

The municipality is about to implement a new traffic scheme in the microcentro — there will be less room to park your car, it will be much more expensive to park it where allowed, and the penalties for violating the parking regulations will be much stiffer. Good for the mayor, but doing it at the same time people are receiving their new municipal tax bills with increases ranging from 30 to 1,500% with respect to the previous month doesn't show a lot of political savvy. And this in turn comes after the failure of the provincial government to pass a new tax law, and just before they try to introduce a new one.

The national government also recently authorized some impressive utility fee hikes for Buenos Aires and its metropolitan area, as public transport went up as well and subsidies were cut. Everybody behind a government desk is trying to squeeze money out of taxpayers to keep things going, at the same time trying not to be too brutal about it because it's an election year y el horno no está para bollos.

With the worldwide economic crunch, the campo crisis still looming, the drought, the prices of exportable commodities plunging to depths unheard of, and the general perception that Cristina K is deaf, blind and clueless, anybody with half a mind can see that 2009 won't be nice. At least the global recession should keep inflation at bay, but even that may fail — Argentina has a way to crash economic models...

13 January 2009

Hot and dry

We're suffering a drought, as is most of the country, especially the agricultural productive areas. It rained last night, and might rain again today a bit, but it was an isolated phenomenon. Right here in Rosario it's still not as bad as it was last year, when grass everywhere was reduced to brittle, desiccated brown fragments and finely-powdered dirt was blowing from exposed patches everywhere, but there are serious problems in the north.

The Paraná's water level is so low you can see the pipes that drain the rain into the river, lying on the sand in the beaches of the northern city. People still go and bathe there, but the usable area has shrunk; five or six meters from the current shoreline, the river starts to get deep and dangerous.

The Paraná's water level is so low you can see the pipes that drain the rain into the river, lying on the sand in the beaches of the northern city. People still go and bathe there, but the usable area has shrunk; five or six meters from the current shoreline, the river starts to get deep and dangerous.

Upstream, in the dry north of Santa Fe, the situation is dramatic. Neither people nor cattle have enough water for themselves, and the crops are dying. Ironically, northern Santa Fe used to be an area of wetlands and forests, but already in the late 19th century logging companies felled a lot of trees (quebracho, mostly) and then the wetlands were drained by canals to avoid floods. After 2002, when soybean became the star crop, agriculture expanded to the area, and cattle were also moved there from the south. But when you remove a forest, you leave the terrain subject to erosion, and without major watercourses you're tied to rainfall.

The drought will reduce the production of most crops. Maize and soybean were planted late because of this, and coupled with a lower yield, that means Argentina will produce a lot less of both (making things worse, the government continues to place administrative obstacles on crop exports, and the international price of agricultural commodities has decreased dramatically). Wheat production has plummeted to about half of the 2007–2008 harvest. Cattle farming is also suffering; the animals languish and die of starvation or thirst, and often farmers prefer to slaughter cows and sell them for what they might be worth. This year there will be one million less calves.

Hmm... still no rain over here.

24 December 2008

Christmas at home

It's been a while since I last wrote, and I feel bad about that, given how often I used to post in earlier times. But such is the way of things.

The last year or so has been busy for me, mostly in the good sense (new girlfriend, new job routine, new places traveled to), but not spectacularly good for news (about the city, or the country or the world as a whole, for that matter). I seem to remember apologizing for a seemingly endless string of depressing political posts. I don't want to do that again.

Christmas season is about to end, thank Jeebus, and truth be told it doesn't seem like "the crisis" has hit that hard. Judging from the sheer volume of the throngs that squeezed along every inch of the downtown commercial streets last Monday (that's when I went gift-shopping myself), there's still lots of spare change in people's pockets for one last spending binge. The soft credits promised by the government have still failed to materialize (and seriously, nobody thinks they will, or at least it's highly doubtful they get past the nicest parts of Greater Buenos Aires) but retired people have got their extra 200 pesos, there'll be a similar supplement for minimum-wage workers and welfare benefits, and it seems the tendency to pay the aguinaldo before the holidays, instead of in January, has caught on.

As for me, I spent an unexpected amount buying little gifts for everyone in the family, which now includes Marisa's parents and her brother's family of three. Back in 2000, when I first got a stable job, and for more than a couple of years after that, I didn't earn enough for such luxuries as gifts, so now I love having the chance, although the act of going around and choosing the actual gifts is still stressful, being such a detail freak.

Since Marisa and I will each have dinner with our own families, and both driving yourself or getting a cab are virtually impossible on Christmas, we exchanged gifts days ago. I promised not to peep, so as to keep the surprise until tonight. There's no-one left at home that believes in Papá Noel (Santa Claus), and of course I don't believe anybody of divine origin was born on December 25, but one comes to appreciate the symbolic importance of waiting until midnight, as is the custom in Argentina, to open the shiny, bow-topped packages and peer inside to see what our loved ones thought we'd find nice or useful.

These days are exhausting, what with the summer heat and the crowded shopping malls and the explosion of red-and-green kitsch everywhere, and it's true that more people than usual feel depressed or lonely at this time of the year. In this sense I loathe Christmas. But maybe we should have more of it. It wouldn't be so special, but maybe one week as each season turns into the next, with less of a focus in overdoing (overspending, overeating, overdrinking) and more of simple expectation and celebration of our continued friendship. Our ancestors (no matter who they were exactly) had a developed awareness of seasonal change; why couldn't we? Imagine four short holiday seasons instead of a protracted one — better for the economy, for our digestive system, and for our inner peace.

Here's to a happy and peaceful Christmas, to all my readers. I'll see you again sooner than expected, I hope.

Labels: argentina, argentine economy, christmas, holiday season, personal

03 November 2008

Nationalizing pension funds: more money for the Kirchners?

It's time again for a depressing anti-government post! This time, about the nationalization of AFJPs (private retirement funds). I strongly feel it's a good idea, and as strongly as that I also feel we must keep it from happening as intended by president Néstor Kirchner. (If you think Cristina's the one in charge, you must be living inside a jar, as we say over here. For months she's been devoting her time exclusively to cutting ribbons to [unfinished] public works and, lately, to writing newspaper articles in praise of her husband's ideas. Néstor is de facto big guy.)

Now you mustn't believe I do this because I like destructive criticism. I'm absolutely for "big government" as Americans call it, and I believe important stuff should never be left fully in the hands of private corporate interests whose creed is "make money fast whatever way you can". Kirchner's government has taken us far in this sense, and that's OK.

The problem with the Kirchner administration is that they always, somehow, manage to turn good theory into bad practice, and for a long while now (and not because the media or the far right are trying to make it look so, as C&K passionately believe) everything they've proposed has been born tainted by association. Or, as in this case, destined to fail before (a good part of) public opinion because common sense and the typical Argentine paranoia will kick in, and all alarms will go off, as soon as the state gets close to our pockets.

About 15 years ago, the law that allowed the creation of the AFJP system was drafted and passed, accompanied with a heartfelt defense of private capital accumulation (the so-called "capitalization scheme") by many who now profess to be old-time fans of the old-fashioned state-regulated collective saving scheme, including many faithful Kirchnerists (flip-flopping is another word for pragmatism — the only thing that can be truly called "Peronist doctrine"). Gobs of money were transferred to private capitalization accounts from the state's coffers, and the AFJPs (Administradoras de Fondos de Jubilaciones y Pensiones) started recruiting associates. The law said if you didn't choose where your retirement funds should go, then it would be automatically assigned to an AFJP; thus millions of distracted workers were signed up for a massive speculative operation. The AFJPs invested money in assets of various kinds and for a while they actually increased their clients' funds, although they charged huge commissions.

Pensions were frozen for ten years, as the economy entered into a low-growth phase, unemployment rose steadily, and finally recession entered the picture. After president Carlos Menem (cursed be his name) got away with murder, president Fernando de la Rúa found the dying economy and, instead of trying to resuscitate it, he finished it off with such nice measures as cutting 13% of pension payments. We all know what happened then... so fast forward to 2003.

Néstor Kirchner passed a series of decrees increasing both salaries and pensions, which were well-received, even as employers complained. The economy took off and pensions did as well. There was a small problem, though: the private pension funds couldn't keep up. They started losing money. The law said that the state must guarantee pension payments, if necessary by compensating (subsidizing) the private funds. So the state poured money into the AFJPs, whose risky investments had proven disastrous (does that sound familiar?), and when the companies began accumulating too much debt, the government forced them to buy national debt bonds. Yes, that's right: the government forced the guarantors of retirement funds for millions of Argentinians to accept what amounted to wet paper in order to rid itself of them (the only other feasible destination for those bonds was Hugo Chávez).

In January 2008, after the scarce enthusiasm that followed Cristina's election had faded, someone near her came up with the idea of "letting people choose" where to place their retirement savings. The Kirchnerists hastily passed a law opening up the choice for everyone: 180 days to take your money away from the private box to the state's bag (or the other way round). And the law also established that, if newcomers to the labor market didn't explicitly choose which way, their funds would go to the state system, not some AFJP. The AFJPs understandably lost a lot of clients, but in all fairness they deserved to, and the law didn't force anyone to accept anything against their interest. It had some other very good points as well, so good in fact that, "better late than never" aside, some of us wondered why it hadn't been passed before. Like four years before.

The answer came easily. Why indeed? Because it was only now that the economy had begun slowing down, while debt payments were looming closer and the whole economic structure was showing the strain. High inflation, high interest rates, no way to get fresh funding for things like the bullet train, and the need to pump more and more money into subsidies for electric power, drinking water, fuel, natural gas and everything else. Néstor Kirchner had always ruled with a big wallet of state money freely available to him, but Cristina's future was uncertain. The fresh funds from the AFJPs, of course, should have never been used to fund the state in any respect other than pension payments, but the new law didn't say anything about that. Already in 2007, his last year, Kirchner had signed a decree allowing the government to divert funds from ANSeS (the social security agency) to expenses such as public works.

After the fiasco of Resolution 125 (another, more desperate attempt to get money for the state) came the worldwide financial crisis. After being deprived of juicy taxes on exports of soybean, both exporters and the government have seen the prices of soybean plummet to half the levels of the first quarter: less and less money! Subsidies on buses, natural gas and power were reduced, but that's not enough; with a world recession looming, and the economy visibly decelerating, it would be economic suicide to raise the prices of basic services. On top of that, 2009 is an electoral year, and that means a lot of wills and votes must be bought. Back then, Néstor and Cristina could campaign all year round, visiting one town after another in provinces with "loyal" governors, handing out multimillion checks without any real oversight, and making sure crowds of bussed-in "supporters" would be ready to applaud their presence; but all that costs money.

The national state keeps about 70% of what the provinces contribute, and what it shares, it does so rather unfairly. Most provincial governments are strapped for cash right now, and more than a few are absolutely dependent, on a short-term basis, on presidential whims when it comes to distribution.

Kirchner's desperation is now becoming noticeable. Initially he ordered the bill that nationalizes AFJPs to be approved and turned into law at once, without any changes. His parliamentary bulldog, deputy Agustín Rossi, first attempted this, then saw it was impossible, and timidly conceded that the government's bloc would accept discussion of the finer points.

Now, the bill seeks to overturn a 15-year-old system with millions of associates, in a context of financial turbulence, and to do so in a matter of weeks, so that all the money from the private pensions can be transferred to the state's social security before the end of the year. Not only does this negate the choice of millions of people who decided to stay in the private companies earlier this year, but it also looks rather suspicious.

Why the hurry? True, the assets of the AFJPs are taking heavy hits from the world's financial meltdown. But those things come and go. It's also true that the AFJPs haven't given their associates what they promised, and that they've engaged in some dubious practices. That's something to be settled with general audits. If you have a critical system that doesn't seem to work as intended, you don't decide to break it. You fix it and keep it going while you prepare the transition. The president can count on ample powers, a Congress controlled by overwhelming margins, and a social consensus that private pension funds aren't a good idea for most of us. I repeat, why the hurry? Cristina still has three years to go.

This administration has frustrated me time after time. I'm really tired of seeing great ideas given such bad names by the Kirchnerist gang. I'm fed up with having to agree with certain people... being forced to be on the same side as some who hold principles completely opposite from mine.

Yet I have no alternative. It's just plain common sense that the Kirchners want the private pensions' money to continue their incessant campaigning for their own permanence. They have no new ideas, no plan, no policies, nothing but a hunger for power that sometimes translates into seemingly brilliant developments, soon marred by corruption and negligence. Are we as a nation doomed to go from one rotten set of politicians to another?

30 October 2008

25 years of democracy

Today it's been 25 years since the formal return of democracy in Argentina. On October 20, 1983 a democratically elected president, Raúl Alfonsín, took office after more than seven years of dictatorship and over half a century of erratic shifts between legal presidents and military usurpers.

My personal reckoning is that, although I was born exactly six months after the coup d'état, I have so far spent four fifths of my life under democratic rule. During that time I've voted quite a few times: three times for president (1999, 2003, 2007), four for governor (1995, 1999, 2003, 2007) and many more, at least once every two years to elect national and provincial legislators, and once every four years to elect city mayors and councilmembers, plus a couple of primaries. My generation is possibly the one that has voted the most times during the entire history of this country.

On the national level I've always either voted for the loser... or later regretted not voting for him. During all this time, this thing that gets called "the democratic process" hasn't offered me much satisfaction. But I don't want to despair. Never has Argentina experienced so many years (a quarter of a century!) of uninterrupted free elections on all the levels of government. We move on and crises hit us and sometimes we'd rather have everything blow apart, but in our heart of hearts we know and wish it will go on no matter what.

I have my reservations and my protests in store and readily available, but today I want to end this on a positive note. For 25 years now we've refused, as a people, to be deprived of our right to choose, and even when all our options look bad, we always have one more chance ahead of us. And that counts.

(El texto original de este post, en castellano, está disponible en Sin calma: 25 años de democracia.)

14 October 2008

Time displacement

By decree of Our Most Reflective Leader, President Cristina of the Unwrinkled Face, and based on the success of last year's Daylight Saving Time scheme, we'll be advancing our clocks and watches by one hour next Sunday, October 19, at midnight (which will thus become 1 AM). Except of course there was no measurable difference in power usage last year, and all we got from DST was a surge in sleep disorders (and, admittedly, beautiful sunsets at 11 PM beyond the 40°S parallel — almost midnight sun without the expense and inconveniences of a trip to Antarctica).

As usual, it's up to the provincial states to adhere or reject this measure. Four provinces (San Luis, San Juan, La Rioja and Catamarca) are almost sure they won't change the time, while Mendoza has already announced it won't — that is, the whole Cuyo region plus the neighbouring Catamarca will stay behind.

Here in Rosario, as well as in Santa Fe City, business owners are complaining as well, and plan to file a formal request to governor Hermes Binner. Most likely that won't change the decision. It would be rather problematic if Santa Fe stayed behind while all of its neighbours don't.

08 October 2008

Argentina's economy: what now?

Everybody's talking about the financial crisis, so I thought I could chip in with my two cents..., especially seeing how our own Argentine government continues to deny we'll face serious trouble. In fact, President Cristina Kirchner has devoted a lot of time to deride, with barely concealed glee, the proponents of globalized laissez-faire capitalism (we must acknowledge that "kicking them while they're down" never felt better) and to defend the Kirchnerist achievement of decoupling Argentina from international market shocks, which would be terrific — if it were true.

First of all, not to despair: we are, as Cristina says, better prepared than ever in recent history for the shock. The problem started outside our borders (we have different problems) and we'll just have to slow down and wait, hoping that they don't spill into our own economy. For example: we need money to pay our foreign debt next year (and it's a lot of money — more than we owed before Néstor Kirchner renegotiated it, because we actually exchanged debt for more debt), and it'll be difficult to get money from abroad or to refinance the debt once again, with interest rates being so high and everybody clutching desperately to their remaining assets; but we still have a fiscal surplus and a trade surplus.

The peso-dollar rate jumped a bit, too, and that will help the trade surplus. There's just one problem — we're dependent on imports of all kinds, so a higher exchange rate means inflation. And one more problem: the Brazilian real has devalued as well, only much more brutally, so Brazil will be able to sell cheaper stuff to us, they won't be able to buy as much from us, and they'll be much more competitive with respect to third parties. Brazil has a long-standing state policy of industrialization; we don't. Brazil can cope with lower or higher exchange rates; we can't.

Yet more problems: our trade surplus feeds our fiscal surplus, via retenciones (export taxes), especially on soybean products. The price of soybeans (as with other commodities) has taken a deep dive, so that means less revenue from exports. China buys most of our soybeans, but China, like all countries around the globe, will start buying less of everything. Less revenue from exports means less available money to (for example) cover the costs of subsidizing inefficient public services and utilities, and funding public works. The national government has already left the inner country to its own devices, delaying or altogether abandoning plans to build homes, schools and such (Minister De Vido lies, as usual); now it's Buenos Aires's turn. Natural gas, drinking water, domestic power, buses, trains, the subway — they'll go up and up, while construction (the engine of Argentina's economic recovery since 2002) will come to a halt. Tourism and foreign investment will suffer as well; people in the US and Europe simply won't have money to spend on Third World countries like Argentina.

There's a political problem as well, because 2009 is a legislative election year, and the Kirchners doubtless had plans to pour money into cheap, quickly-unveiled public works all over the country, as Peronists are fond of doing; that just won't be possible in this scenario. Least of all if the opposition gets to revise the budget, which contains certain provisions deserving a "best fiction" award, plus the infamous "superpowers" that let the Chief of Cabinet move around huge chapters of the budget under the excuse of an economic emergency that supposedly ended years ago.

All in all, it looks like the next months will bring a "plateau" in Argentina's so far swift growth, and the Kirchnerist government will have to deal, for the first time ever, with a tight budget. It's easy to play when you have cards, as we say over here. The feeling of opportunities for true growth, for industrialization, for true redistribution of wealth, wasted and lost and now unlikely to return for a few years, is almost unbearable.

29 June 2008

We have smog

Smog isn't a common word in Spanish. We're familiar with it but nobody really uses it. Our large cities naturally have some, always, but it tends not to be that visible. Buenos Aires and Rosario are on a plain beside large bodies of water and with no natural obstacles to keep airborne pollution in its place. I don't know how Córdoba manages that, but I've never heard of it having smog despite being inside a big hole.

When the owners of vast tracts of land in the Paraná Delta's islands started burning the scrubland to prepare those lands for cultivation or pasture, we got to know smog. This is etymologically correct smog I'm talking about — it's smoke plus fog, the latter being caused by cool weather and high humidity.

Now some early morning fog makes for great pictures, but smoke and ashes aren't that healthy, especially at the beginning of winter, when people's respiratory systems are already oversensitive. I didn't feel anything funny myself while taking the photo above, but then most of the blurry stuff was true fog. The lamppost you see near the center of the picture (above the guy's head) was only one block away. When you turned round, the view was much clearer, but a faint greenish-gray screen was readily apparent.

Besides that, I swear I'd never heard of so many plane delays due to smog. These are bad times for road trips too — the road blockages set up by farmers and truck drivers have stopped for the moment, but in this region (say from Rosario to Buenos Aires and around) there's so much fog and smoke that roads are totally or partially closed to traffic every day, until the sun dissolves some of the stuff. And traffic accidents are so common that the radio broadcasts the body count next to the weather forecast.

(I object to calling these "accidents", since in most cases they're caused simply by disrespect for the law, overconfidence and disregard of basic safety measures, for which Argentinians are infamously known. If you find yourself inside an airborne gray soup, the right thing to do is flash your lights appropriately and stop beside the road, no matter if you're late for work or the start of your vacations. And if you see someone stopping beside the road ahead of you, you should consider doing the same. The Argentinian's typical reaction, however, is to trust his good stars, disregard a few near misses, curse the weather, and finally crash into someone and blame the state for not forcing him to stop.)

The fires on the islands are obviously not being monitored by anyone. On any given day it's easy to spot two or more columns of smoke rising from different places along the floodplain of the Paraná, opposite the coast of Rosario.

The fires are intentional or derived from intentional ones. Though the weather might be humid, it hasn't rained a respectable amount for months (in fact the north of Santa Fe has been declared an emergency area because of the drought), so all that withered grass and plants and trees are prone to ignite at the very lightest touch of flame. The wind usually carries the smoke away toward the south (to Buenos Aires), but part of it always remains here and affects the coastal areas of the city. If I can see where it comes from, then the authorities (governors, mayors, police, judges, prosecutors, ecological management offices) can see it as well. Why does nothing happen?

20 June 2008

Flag Day 2008 (no pictures this year)

For reasons unknown to me, Argentina commemorates great men and their deeds at the date of their deaths rather than their births or the actual events that made those men great. So this death anniversary is Flag Day. I wrote about it last year (Flag Day 2007), which was a big deal because it was also the 50th anniversary of the construction of the Monumento a la Bandera (Flag Memorial).

This time, however, I refrained from attending the ceremony and the parade. Besides the awful weather (cold, windy, cloudy, and threatening to rain) plus my own concern for my health (I'm still recovering from the cold I caught last weekend), there was too much going on for it to be just a festive meeting of the citizenry.

Until a few days ago, nobody knew whether Cristina Kirchner would preside over the official celebrations in Rosario, as protocol dictates. The "man in the street" view was that she would either (a) employ any excuse to avoid coming to Rosario, where she'd meet harsh popular opposition, or (b) come here bringing along a couple tens of thousands of "supporters". The latter hypothesis was likely, given that the shock troop leader in the service of the Kirchners, Luis D'Elía, had vowed to come to Rosario today to cheer for the President, "defend democracy" and "vindicate the flag", defiled by the May 25 meeting. However, D'Elía went overboard with his call to "take up arms" against those who wanted to "destabilize the government", and the Kirchners backed away from him.

Then the President went and presided over a partisan rally, two days ago. It was organized and paid for by the Presidency, i.e. our taxes, but it was undoubtedly a Peronist rally. The CGT union even decreed a national strike (it was effective only in Buenos Aires) to allow workers to go see Cristina. This rally was seen as both a provocation and a confirmation that Cristina would only address her selected supporters from now on. The idea that she might have thousands mobilized again, to Rosario, 300 km away from her only real center of political power, and along a national road that is blocked in a hundred places by people hostile to her policies, was beginning to sound ridiculous.

Moreover, when Rosario was designated as the center of the agricultural protest, about 200,000 people gathered here on May 25. The call to attend the last pro-Kirchner meeting was refused by the local unions, who said it was divisive and inappropriate, so Cristina could expect no help from them on Flag Day. And the common public doesn't like patriotic dates turned into political meetings, and doesn't like Cristina's speech style.

The middle class, in fact, hates Cristina with a passion. Even the local leftist movements are against her in her fight with the agricultural sector. The governor of Santa Fe, Hermes Binner, is a Socialist who supports the legislative debate of the export taxes that Cristina would've chosen to impose. The mayor of Rosario, Miguel Lifschitz, is also a Socialist. Cristina, like her husband, is used to have local authorities on her side wherever she goes — authorities that can be counted on to fill the spaces at rallies with cheering people.

So she chose not to come. The excuse was "bad weather" — plausible, but nevertheless just an excuse. Two days ago, when "bad weather" couldn't be assured, the national officials in charge of protocol and presidential security were already conspicuously absent, when usually they should be planning and coordinating with local police and municipal officials here in Rosario. Then it was announced that Cristina would be instead in Quilmes, near Buenos Aires, in the afternoon. And finally, she moved once again and decided she would do some other minor stuff in Hurlingham, because it's going to rain and there's a roofed stadium in Hurlingham. (La Nación says the Flag Day celebration was moved to Hurlingham. That, as someone pointed out, is incorrect. What moved was Cristina and the presidential political machine, not the official seat of this patriotic celebration, which is duly held in Rosario, as has always been the case.)

So she chose not to come. The excuse was "bad weather" — plausible, but nevertheless just an excuse. Two days ago, when "bad weather" couldn't be assured, the national officials in charge of protocol and presidential security were already conspicuously absent, when usually they should be planning and coordinating with local police and municipal officials here in Rosario. Then it was announced that Cristina would be instead in Quilmes, near Buenos Aires, in the afternoon. And finally, she moved once again and decided she would do some other minor stuff in Hurlingham, because it's going to rain and there's a roofed stadium in Hurlingham. (La Nación says the Flag Day celebration was moved to Hurlingham. That, as someone pointed out, is incorrect. What moved was Cristina and the presidential political machine, not the official seat of this patriotic celebration, which is duly held in Rosario, as has always been the case.)It's a pity that the President misses the true celebration. I for one would've considered going if she came, though mainly to boo her. Some of my fellow citizens would, I think, as well. Others were understandably afraid that the Kirchnerist mob would hijack the celebration and disallow the expression of dissent. And yet others were planning to boycott the President's coming to Rosario by hanging black flags on the balconies, instead of sky-blue-and-white Argentine flags, or by simply leaving when she began her speech. She's spared us from choosing among those sad alternatives.

Yesterday I was thinking that Rosario has traditionally been a progressive city, with critical citizens, who never receives attention except on Flag Day, when protocol compels the chief of state to be here for a couple of hours. In ten years Carlos Menem came three times, and the last one he was basically ignored (the weather was awful, like today). Fernando de la Rúa never came, since he couldn't have gotten out alive. Néstor Kirchner came twice, and only the first time he was greeted with enthusiasm; the second time he had to bring his occupation troops with him. Cristina backed away already.

I was writing to someone who lives abroad about this, and I said I felt this feeling of refreshing insolence against the government. Not the bitter anger of people who don't know what the government will do to them, but a healthy mixture of disrespect and rebelliousness. Indeed, if one isn't free to insult one's own authorities for fear of being accused of subversion, what's left? Cristina is afraid of coming here to Rosario, where she'd receive the public punishment she deserves. And I'm proud of that.

16 June 2008

80 years of Che Guevara

Too tired to write it all down now, but here are the pictures I took during the celebrations for the 80th anniversary of the birth of Ernesto Che Guevara, quite possibly the most famous citizen of Rosario. It's an embedded Flickr slideshow. If that doesn't work, try 80che: 80 years of Che Guevara. New pictures may be added tomorrow.

10 June 2008

I want to believe

Cristina, you are a genius! You just sent those coup-inciting filthy rich farmers packing, and you unveiled a master plan that will show Argentinians the extent of your generosity, vowing to put those billions of dollars of tax exports to use on the things the poor and the struggling working class need — roads, public hospitals, unexpensive housing. If only I could believe you!

Cristina, you are a genius! You just sent those coup-inciting filthy rich farmers packing, and you unveiled a master plan that will show Argentinians the extent of your generosity, vowing to put those billions of dollars of tax exports to use on the things the poor and the struggling working class need — roads, public hospitals, unexpensive housing. If only I could believe you!

As I write this, I've just finished hearing President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner's speech on the national broadcasting signal (Cadena Nacional) which she had used only once before. I'm posting it now, on the day after the speech, because I just posted something else, something personal about my weekend, something of no importance.

I must say this — Cristina showed that she's not beyond reflection and change, and everybody took note of that. That that simple fact is a huge relief shows clearly how low our political culture has gone. The President, in the most contorted fashion, acknowledged that the government made a mistake, and asked for forgiveness to anyone she might have offended. I bet several million of my compatriots had never dreamed they'd hear such words coming from a Kirchner.

Now for the real content of the speech, things aren't so bright. Before Cristina began, the official spokesman read aloud a decree that will be published tomorrow, creating a "Social Redistribution Programme", which will be funded by the mobile tax exports on soybean whenever they climb above the 35% mark, and will be in charge of building public healthcare centers, roads and "popular homes". The Programme will be "decentralized", said the Prez; the national government will leave it to the provinces and municipalities to implement what they need. So far, so good.

Now, the Kirchners have been doing this kind of "federal decentralization" for years — it works by giving money to politically obedient governors and denying it to provinces ruled by the opposition (opposition doesn't mean just a different party — anyone who disobeys is opposition). There's no sign that this time it will be different. The Programme's funds will be administered mainly by Federal Planning Minister Julio De Vido, who has the power to do whatever he wants with great chunks of the budget.

At no time during her 30-minute speech did the President explain why this plan is presented to the public now and not before, or why the extra couple of billions that might be collected from farmers couldn't be replaced by the US$4 billion they're spending on a bullet train for the rich. It's obvious the Programme was made up in the last few days, and we Argentinians know perfectly well that such great plans never come to fruition, mainly because middlemen divert (steal) the funds.

Cristina said we're not in a crisis anymore, which is right, I believe. If so, however, our useless, yes-people-filled Congress should reclaim its duty to manage the national budget, which they gave away (in violation of the Constitution) years ago because we were in an emergency. The emergency is over, right?

Moreover, the need for a paternalist, strong-handed government is over as well. We don't need an Evita lookalike implementing her version of a Great Leap Forward. We need a federal state that lets the provinces have their own money and manage it, not granting them leftovers from an unconstitutional tax. Only allied governors and government-addicted mayors were invited to Cristina's speech, to nod and smile and applaud. No room was allowed for dissent. The Kirchners firmly believe they're the only ones who know how to run the country, and they refuse to hear, let alone follow, other people's opinions.

Cristina did one thing right: she noted that it all began because a certain specific group of people, who on average are doing quite well compared to the average, refused to accept that the state took away part of their profits (again). Of course, we all knew that, and it's a testimony of the profound ignorance of the Kirchners that they turned a focalized reaction against tax collection into a divisive countrywide revolt that brought down their image and caused huge losses of money and time for everyone.

Here are links to the coverage of the speech, in Spanish:

- El Gobierno anunció que las retenciones móviles financiarán un plan social (La Nación)

- Cristina anunció un plan social con fondos de las retenciones (Clarín)

- La presidenta anunció un plan social solventado con las retenciones móviles (La Capital)

- Cristina "descentralizó" la distribución de las retenciones y pidió perdón (Rosario3)

- "El error fue la ingenuidad de tocar la renta extraordinaria de un sector" (Crítica Digital)

- and this article published this morning, which follows Cristina's speech so closely that it's obvious it was leaked to the most government-friendly newspaper: ¿Podría pasar? (Página/12)

01 June 2008

Che Guevara's statue

The bronze statue of Ernesto Che Guevara arrived in Rosario, its city of birth, today, after four days travelling by boat up the Paraná river from Buenos Aires, where it was made. I wrote about el Che's monument in February, after I'd read about plans for the celebrations of Ernesto Guevara's 80th birthday (June 14th).

The statue came at noon, and I guess I could've been there, but didn't know and I was exhausted, and expected at home for lunch. There was a welcome celebration at the Flag Memorial Park, and then a parade that took the statue to the place where it will be set up, its own Plaza Ernesto Che Guevara within Parque Yrigoyen, on 27 de Febrero Blvd. The next two weeks there'll be a whole lot of Che Guevara-related activities organized by the Municipality, which is (I'm told) spending its last cents on these events. (The economy is going badly, what with inflation and public employees' pay rise and all.) Yours truly expects to be present at least in some of them.

The statue of Che Guevara arrives — caught by a fellow Flickr'er!

26 May 2008

May 25: the people's meeting in Rosario, and Kirchner's show in Salta

Yesterday, May 25, the campo held its meeting here in Rosario, at the Flag Memorial. The four main agricultural organizations and many others called for people to come from all corners of the country. Although the initial protest was triggered by the increase of the tax export on soybean, the government handled it so badly it ended up turning it into a movement that demands global changes in all areas: differential tax exports, subsidies or tax exemptions for local production, help for smaller producers to avoid the concentration of land, a comprehensive policy for agriculture and livestock farming, and a general change in the style of government of the Kirchners.

Marisa and I had arranged to have breakfast at 8 AM with the Rosarigasinos and four visiting photographers coming to Rosario via Buenos Aires, at a bar located on Belgrano Ave., which comes from the south and leads to the Flag Memorial. That's where the attendants to the campo's meeting were coming. The morning was cold but the wind was mercifully calm. Even at so early a time, we saw bus after big bus bringing people to the meeting, plus tractor trucks old and new, plus cars, and people marching on foot with Argentine flags, banners and signs.

We took our breakfast and then went out to check out the masses. The morning was splendid; the air was filled with expectation, and tens of thousands of white and sky-blue flags were flying. We took a detour around the back of the Flag Memorial to avoid the greatest concentration of people and heard the announcer over the loudspeaker, thanking the attendants and reading the banners with the names of the places where they'd come from. Many were from small towns in Santa Fe, some of which I'd never heard about before; many from the superproductive area of southern Santa Fe and southern Córdoba, but also people from the drier north, from Chaco, Entre Ríos, Corrientes, from the rich lands of north and central Buenos Aires, from Tucumán and Salta in the far northwest, and from Neuquén and Río Negro in the southwest. There were whole families and many older couples, plus heterogeneous groups marching together. Every time the announcer read the name of a town there was a roar coming up from some place or other in the crowd.

I took a lot of pictures and some video, but I didn't stay for the speeches. Our visitors followed us down Belgrano Ave., along which people continued to arrive past the police barricades. There was a rumour that the organizers wanted to start early because then President Cristina Kirchner would be speaking on the official TV channel, which requires all others to cut off their broadcasting. I don't know what became of that, but I learned later that Cristina, presiding the celebration in Salta, spoke for only 14 minutes in front of a crowd formed by a majority of people who were paid to be brought and planted there to applaud her.

Cristina's crowd waved banners with political legends or signs noting who had paid for them to come — Kirchnerist mayors and union leaders who always need to display their loyalty to whoever's in charge to continue receiving their pay. I didn't even bother to listen to Cristina's speech later; in any case, her diction and style are so irritating, and her every sentence so full of pretense, that I can't stand her for more than five seconds.

Our meeting (the one in Rosario were the people came by their own will and only waved Argentine flags) gathered 200,000 people according to the police, or more like 300,000 according to the organizers. There wasn't a single incident or disturbance among the attendants or towards other people or the host city. Kirchner's disgracefully political meeting gathered 150,000 according to the government, although the police said it was more like 70,000 (we know how the Kirchners love to tweak numbers in their favour...), and as seems to have become customary in Peronist meetings, some tough guys from the truck drivers' union (whose leader sat near Cristina) engaged in a brawl with some other tough guys paid to attend by the Kirchnerist government of Tucumán.

The coverage: the openly Kirchnerist Página/12 and its child Rosario/12, the local La Capital, the also local, unfortunately titled Rosario3, the outraged conservative La Nación, the arch-enemy of everything that's good, Clarín, and the BBC.

I have more to say about this (you were fearing that, weren't you) but I'll shut up for today.

19 April 2008

Smoked!

Wake up and smell the smoke, if you haven't! I've noticed this blog has many occasional (or one-time) readers. So, for the ones just tuning in, this is about the fires covering the Argentine littoral (and its capital) with smoke. Here's a few pictures, all taken from the coast of Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina, today around noon. We're 300 km north from Buenos Aires (whose name has never seemed so much of a joke as nowadays, he he...). A seamless cloud of gray smoke covers the eastern horizon. The islands of the Paraná delta are on fire, because the owners of the fields have once again employed the ancient method of clearing scrubland with fire.

The Rosario–Victoria Bridge has been re-opened to traffic after a couple of days of being partially or totally shut down. You can barely see it, though, from this point located only 7 km away. Remember this is noon, and the picture has been enhanced for contrast.

You can't go from the south of Santa Fe to Entre Ríos if you can't use the bridge — you have to take a huge detour up to Santa Fe City and cross the river though the Subfluvial Tunnel.

In Rosario we've been enduring the smoke and the ashes for years, but it was only this time that the fires got completely out control and the smoke reached Buenos Aires, thus instantly turning this issue into a national emergency. The presidential minions quickly blamed the farmers (who seem to be guilty of everything that's wrong in the world today, from child hunger to environmental destruction) and Queen Cristina herself ruined her hair by flying over the affected area on a helicopter.

Not a word was heard from the unanswered complaints of Rosario's municipal government over the years, or the complete lack of suitable responses by the Kirchnerist governors of Entre Ríos (both past and present) regarding the fires being intentionally started by farmers in their jurisdiction. They knew who they were, and although there was a judicial ruling protecting their irresponsible actions, those things can and should be fought in court. Anyone with a minimum of foresight could see this coming.

Firefighters are now trying to contain (not extinguish) the many fires throughout the delta's islands. It's impossible to do anything else. Planes cannot go there with all that smoke. The place is a tangled maze of wetlands and streams. I hear we're getting help from the federal government; up until recently there were only volunteer firefighters from Santa Fe and Entre Ríos, the former heavily outnumbering the latter, although (as I said and will keep on saying) the islands are in the jurisdiction of Entre Ríos and whatever happens there falls entirely under the responsibility of the government of Entre Ríos.

Here you have another picture, this time facing due north, so you can see the visual effect of the smoke. The sky is naturally colourless at this time of the day, but the horizon's gray is not natural. The old piers and the silos on the left are closest; the silos and the buildings around are former port facilities. They're not far away, and you can see they're already veiled by the smoke.

A little more to the right you can see the silhouettes of four towers; they're the illumination towers of Rosario Central's Gigante de Arroyito stadium. On the center-right you have the Sorrento thermal power plant, and then a cargo boat anchored nearby. At that point the coast describes a curve, so what you see right of the boat is much farther away. On a clear day you can see that shore clearly, though, but these days the smoke is noticeable all the time, subtly when you look at buildings a block or two away, and as a thick gray cloud when your line of sight is clear, as in this case.

So far I don't know of people suffering any grave consequences from the smoke. Fortunately most of it is being blown southwest towards Buenos Aires, leaving us with a subtle cloud that runs all along the coastal area of the city, including downtown. It's not pretty, and sometimes it smells, but we can breathe.

In case you didn't like my pictures, here's one from a better perspective, by NASA. The tiny red circles are fires. Rosario is the grayish splotch to the right of the leftmost one (above the ra in Parana), beside the green mass of the delta.

15 April 2008

Juan Domingo Perón according to The Simpsons

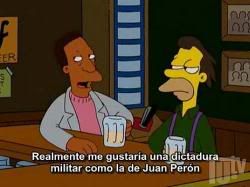

There's an outrage here over the 10th episode of the 19th season of The Simpsons. It seems Homer's friend and drinking buddy at Moe's, Carl Carlson, thinks Juan Perón was a military dictator and his government "disappeared" people. So far the episode has aired only in the original English version in the United States, but already a Peronist representative wants it censored in Argentina. Clarín (posing as anti-government these days) throws an oblique dart at Peronism, misleadingly titling their coverage of this news "They want to ban The Simpsons", which was probably intended to match the censorship request with what Venezuela did (banning the whole series, and replacing it with the moronic Baywatch). The 30-second video segment was posted by Perfil.com on YouTube, but it was promptly removed as a copyright violation.

There's an outrage here over the 10th episode of the 19th season of The Simpsons. It seems Homer's friend and drinking buddy at Moe's, Carl Carlson, thinks Juan Perón was a military dictator and his government "disappeared" people. So far the episode has aired only in the original English version in the United States, but already a Peronist representative wants it censored in Argentina. Clarín (posing as anti-government these days) throws an oblique dart at Peronism, misleadingly titling their coverage of this news "They want to ban The Simpsons", which was probably intended to match the censorship request with what Venezuela did (banning the whole series, and replacing it with the moronic Baywatch). The 30-second video segment was posted by Perfil.com on YouTube, but it was promptly removed as a copyright violation.

I think this is all very stupid, though I can understand the concern. Just to clarify the debate, Juan Domingo Perón was democratically elected president on three occasions. True, the second time he ran for re-election after having the constitution reformed specifically for that purpose by a fanatically loyal Congress, but it was all legal. And it's also true he wasn't really a fan of tolerance or a champion of free speech, and he was a fan of Mussolini's administration, and didn't show any great dislike for the German Nazis until they lost the war.

Under Perón, dissidents were harassed, intellectuals were forced to exile, and people lost their jobs if they were outspoken in their opposition. The media were censored. The government's bullies were free to manage the streets. Nothing unusual in that time and age, or even today in many places. And, as far as we know, Perón's administration didn't have people abducted and nullified. Harassed, beaten, incarcerated, even incidentally tortured, but not in great numbers, not by explicit orders from the top, not systematically. Comparing Perón with even the "softer" dictatorial governments we've had in Argentina is misleading, and suggesting a similarity with the latest (and internationally best known) dictatorship is a gross exaggeration.

And, as far as we know, Perón's administration didn't have people abducted and nullified. Harassed, beaten, incarcerated, even incidentally tortured, but not in great numbers, not by explicit orders from the top, not systematically. Comparing Perón with even the "softer" dictatorial governments we've had in Argentina is misleading, and suggesting a similarity with the latest (and internationally best known) dictatorship is a gross exaggeration.

Still, what's the problem here? Americans are notorious for their ignorance of international issues, and the history of their neighbours in Latin America is just one of those issues, even when the U.S. helped shape it by their constant interference. The Simpsons only reflect that real fact. After Carl displays his crude ignorance of Argentine history by commenting on the "disappeared" of Perón's time, Lenny tops it off noting that, besides that, Perón's wife was Madonna! And Carl and Lenny are two drunks, for Jeebus' sake! Two ignorant drunks in an animated series that mocks American culture. Remember the episode when Carl and Lenny are Buddhists, Richard Gere is meditating with them, and Lenny doesn't know who the Dalai Lama is, or indeed, who Buddha himself is?

Censoring the Perón episode would be ridiculous. If Peronists don't want the name of their leader smeared, let them fight for education, so that children learn unbiased history from books and not from TV series. It's not like Perón had a terrific record on that respect — when he was president, textbooks were filled with hagiographic views of him and his wife, and nothing else could reach the public. When he was toppled by the military, this cult of personality was abolished and even the possession of pictures of Perón and Evita was forbidden.

Censorship of any kind is wrong, and ridiculous: it didn't stop Perón from falling, and didn't stop the military from being toppled in turn. Our representatives should be doing much more important things than watching The Simpsons for historical accuracy.

07 April 2008

Eye of the storm

Now that the farmers are off the roads and the president is off her soapbox (the farmers are hastily harvesting; the president is busy in Paris — see, I can even alliterate parenthetically!) I'll say some things I've been holding up about this mess we've all gotten into.

Now that the farmers are off the roads and the president is off her soapbox (the farmers are hastily harvesting; the president is busy in Paris — see, I can even alliterate parenthetically!) I'll say some things I've been holding up about this mess we've all gotten into.

I say all of us, because countryside or town or big city, rich or poor, oligarch or proletarian, tax-burdened or welfare-assisted, we can't escape one another. Even Cristina Fernández de Kirchner has to come back from Paris and face the country she was elected to govern.

I'm not going to discuss the illegality of blocking roads. That's ridiculous, in a country where everybody has been blocking roads to ask for whatever they felt was their right since 2002. It may be a nuisance or a huge inconvenience, but the farmers did it and they had reasons.

What political analysts say, and they must be right, is that people block roads (an extreme, disruptive form of protest) because they've found that's the only way to get the attention of those who can solve their problems. And that's because those who are supposed to represent them (us) aren't doing their job. Not a single governor, deputy or senator reacted to the strike of the campo to understand what their constituencies were telling them. Politicians are supposed to have quick reflexes in this field. Our politicians, however, have had it easy. That's bound to change soon, I expect.

Cristina, for example, delivered an aggressive speech when she had to go for appeasement and dialogue. She was met with rage in the countryside, and banging pots and pans in some of the big cities. Her answer was to organize a show of strength, bringing thousands to applaud her, not without first letting that rabid classist bigot Luis D'Elía loose with his band of thugs. Her ministers publicly defended D'Elía's mob tactics. Deputy Agustín Rossi, instead of representing his district (Santa Fe), turned into the de facto Kirchnerist Political Commissar and went around attacking the critics. The president gave another speech where, after insulting the farmers and the cities' protesters in several ways, she invited the farmers to dialogue in the most affected way.

All this time, nobody tried to, or was able to, get close enough to Cristina or the members of the Cabinet to explain them that this is no way to handle a country in flames. Cristina continued to believe that she, her husband, that filthy rat Alberto Fernández, and that pathetical rag doll of an economy minister Martín Lousteau, were basically right.

The Kirchners don't know how to deal with a normal country. In the crisis, Néstor Kirchner fared well because he was stubborn and didn't fear bending the rules. He started making mistakes when the waters quieted down and the "normal" troubles began creeping in, such as inflation. Cristina received an isolationist government, and eagerly embraced it. She's aware of her surroundings, of the typical urban politics of Buenos Aires, of his allied robber barons encroaching on the metropolitan area, of large-scale political ties with the quasi-feudal governments of the outer provinces. Nothing else. And yet she and her team seem to think they can micromanage a country like Argentina just by tweaking inflation figures, paying or pressuring the media to publish their version of the truth, keeping hold of a few governors of provinces chronically dependent on federal relief, and periodically forcing busloads of unionized workers and squadrons of welfare slaves* to attend meetings with banners inscribed "VIVA CRISTINA" to show the rest of us how powerful she is.

* If a strong union has a presence in your company, and said union is allied with (or bought by) the government, your union delegates will come to you and suggest that you should march with the guys and cheer for Cristina in the upcoming rally, for which they'll supply transportation to and from, as well as drinks, some food, and maybe complimentary hats. If you're a poor person enrolled in one of the many social movements that were born of the 2001 crisis, and which the government controlled by delegating distribution of welfare and favours on their leaders, then said leaders will come to you and suggest that you should go and cheer for Cristina, too, to show your appreciation for the hand that feeds you. That's how it's done. I mean, poor people gathering freely, for free, just to applaud a filthy-rich politician? In Argentina, Land of the Ever-Complaining? Please.

It doesn't work. It can't. A sizable minority of Argentinians hate Cristina's guts because she has a past of leftist militance, because she's a Peronist, because she relies on the strength of the "insolent poor". Peronism is divisive — not a topic I can deal with. A few hate the Kirchners because they interpret their human rights policy as revenge — the revenge of "terrorist sympathizers" against the state terror of the 1970s. Others don't like how the government tolerates the requests of poor people (pickets and disruptive demonstrations) and encourages "laziness" through welfare, while "decent working people" have to bear with increasing inflation and insecurity and feel nobody brings answers to them. Some criticize the fine points, or the whole layout, of the economic policy. The opposition is a complex mix, and though disorganized, it's not an isolated minority that can be scared by hired crowds.

Cristina Kirchner threw them all into a single bloodied bag. I found myself inside that bag, next to really despicable people, and I didn't like it. She still doesn't understand. She's been bringing back a really dangerous cocktail of ideas from the past, mixing in some unsuitable modern ingredients, stirring with liberal doses of misguided rhetoric, and serving it to people unable to resist the punch, or to people who believe that such ideological cocktails are passé — for which she only gets a complaint and loses a few customers, while 30 years before she would've had the whole bar set on fire.

We're now at the eye of the storm. There were the pickets, the roadblocks, the milk being spilt beside the road, the thousands of starving chickens being killed, the empty supermarket aisles, the cacerolazos, the displays of intolerance and exaggerated outrage, the marches and countermarches, the speeches, the awful media coverage. Then came the truce. Thirty days. The government wasted a week already. The opposition is moving together in Congress. Cristina is in Paris, looking all stateswomanly and probably shopping for jewelry in her spare time.

I have so much more to say about this... I'll leave it for another day. It's so complicated, I tell you, I don't want to ramble, and still, just see what huge mess I've just written.