The other day I was visiting Rob's blog and I saw he'd posted a video about poverty in the province of Chaco. It was really strange to watch this report of something that's happening quite literally in our backyard... in English, by an Argentine journalist, via Al-Jazeera. I knew the reporter, Teresa Bo — I think I saw her once before but I didn't remember who she worked for.

Rob subtitled his post "Another thing I had no idea about", which is not surprising given he's just gotten here from a different country and he hasn't left Buenos Aires (that I know of). What is surprising and disappointing is how Argentinians themselves seem to ignore this as well.

Chaco is a province located north of Santa Fe. It belongs in a larger biogeographic zone called the Gran Chaco, and within it, in the Humid (or Low) Chaco, which is humid only relative to the arid High Chaco.

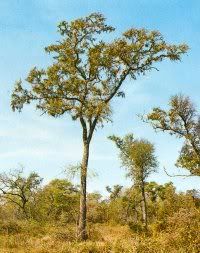

Red quebracho (Schinopsis balansae)

Red quebracho (Schinopsis balansae)Without government control, and given the lack of knowledge of basic ecological facts at the time, La Forestal destroyed the Chaco forest. When it left, in 1960, the quebracho trees were gone, the soil was absolutely degraded, the land had become a desert, and the population was desperately poor.

The main aboriginal group in Chaco are the Qom tribe, who are known as Toba — a derogatory term imposed by the technological more advanced and aggresive Guaraní. The Qom started migrating south as economic conditions worsened in the 1950s, establishing themselves in the outskirts of larger cities. There's evidence that, in the 1980s and 1990s, the government of Chaco encouraged them to abandon their lands and went as far as paying them a one-way ticket to Santa Fe and Rosario, where they joined their previously settled relatives in villas miseria (shanty towns). It was better for them to live in precarious homes made of corrugated iron and cardboard, scavenge for food in someone else's garbaga and work long hours in unqualified jobs in the big city than starving without hope of assistance or enduring alternating drought and floods in the middle of their desertified forest. In Rosario they found a robust public health system, an abundance of free schools for their children, and jobs.

Villa miseria (shanty town) in Rosario, originally a Toba settlement

Villa miseria (shanty town) in Rosario, originally a Toba settlementWhat they didn't find was a return to their ancestral ways, which worked fine for them before their lands were ravaged. Like most of the rural poor that migrated to the cities, they fell prey to the political clientele system, and their children became accustomed to beg in the streets, to use alcohol and illegal drugs, and to expect nothing from the future.

This post is getting too long and sad, so I'll reserve the rest of what I'd written for tomorrow or the day after that. It concerns the local Qom and their involvement with one of those power-hungry religious characters that seem to be attracted to poverty and despair (not, not Padre Ignacio).

Pablo -

ReplyDeleteDo the kids from the villas have to go to schools closest to where they live, or can they go to schools all over Rosario?

John

John - Parents may, in principle, get a place for their children in any school, and the people of the villas are no exception. However, since they're so poor, they tend to send them to schools in the neighbourhood so they can avoid taking the bus. Schools in poor parts of the city often also provide breakfast and/or lunch for the children. Sometimes it's just a cup of warm milk and a piece of bread, but it's food.

ReplyDeleteThis unfortunately tends to keep the poor in their own ghettos.

Pablo, muy bueno tu blog. ¿Recordás, sabés algo sobre Arturo Paoli y su trabajo con los hacheros de La Forestal en Fortín Olmos? Me encantaría tener un comentario sobre eso.

ReplyDeleteGracias,

mdiana