Back from the weekend, I can't help but thinking that plans and schedules are really useless in Real Life more often than one might guess, and that indeed the joys of Real Life are usually to be found in the chanceful parts. I say this because I managed to pull off a nice weekend despite the fact that my ideas for it got completely scrambled.

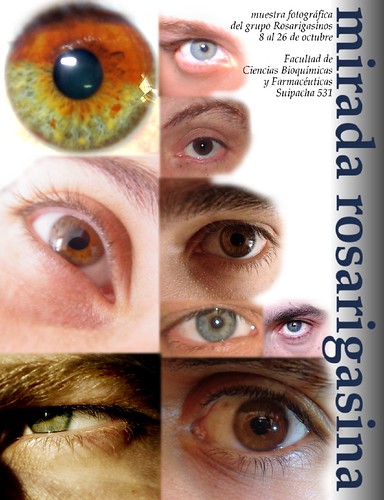

As I said earlier, the Rosarigasinos are planning a photo exhibition. We'd scheduled an informal meeting in a bar, Saturday morning, to get all of our pictures together and collect the money for high-impact plastic sheet we're going to use to frame them. But since I was having my friends over for a late birthday celebration on Friday night, I took them beforehand to Facundo's place (Facundo is one of the Rosarigasinos). First unplanned occurrence — I changed my mind at the last moment and chose a different picture instead of one I'd selected before. I'd given quite a lot of thought to it, since we only get to show three photos each, but I looked at it and found it nice and Facundo concurred, so I dropped the other picture.

The picture I decided to use instead of the other

The picture I decided to use instead of the otherFriday night dinner was pizza and bits of the assorted crap that goes with beer. One of my friends has a 3-year-old child who is generally a good girl (this time was no exception), but has the horrible habit of junk food which afflicts so many children her age, and which the mother cheerfully allows. Faced with greasy cardboard-like chips, delicious home-made pizza, sausages in tomato sauce, meatballs and peanuts, the little junk addict went straight to the chips. (Even the peanuts would've been better. They've got Omega-3 and stuff.) I'm of the rather extreme opinion that children shouldn't be allowed to eat junk food, drink Coke or watch TV until they're at least 5, but it wasn't my call. So I only said to my friend, as she motioned for more chips, "Is she

not going to have

any real food?".

Saturday morning, second unplanned occurrence — I woke up after only 4 hours, too late to reverse my decision and rush to the Rosarigasinos' gathering, and too early to do anything else. Got up, had breakfast, and then I decided to go

jogging. Bad idea. Lots of pizza and peanuts washed down with beer at unusual times, plus little sleep that gets your head alert again but doesn't rest your body, meant that I was tired too soon. I did manage to run all the way, about 5 km, stopping every now and then. It was OK; I needed to resume the habit some day.

Got home, took a shower, had lunch, then went to sleep again. I figured I was going to get out in the evening, and on Sunday either go on a photo trip to a nearby town (with a friend and her photography classmates) or have grilled fish for lunch (with another friend), so I'd better get decent sleep or I'd be wasted. Third and fourth unplanned occurrences — the first friend I called wasn't sure he could go out due to a family problem; the second one had his cell phone turned off or not working. Fifth unplanned occurrence — no fish; my friend of the fantastic grill was suddenly going to have his parents over. Sixth unplanned occurrence — my friend of the photo trip had second thoughts and nobody in her group had arranged anything, so the trip was basically cancelled.

Fine. So I go to sleep early (on a Saturday night! what a sin!) and next day, facing a sunny Sunday with nothing to do, I start by having copious breakfast and then go out to walk and take pictures. I grabbed a few ones of the Ludueña Stream. You can see the difference in level from the first picture, taken where the open channelized section becomes piped underground, and the last picture, where the stream ends in the Paraná. Those are a mile apart at most. The channel is a real dump when it's low, as it's now (compare to

the time of the Great Rains). The little harbour in the mouth of the stream was being dredged less than a month ago, but the water level seems to be OK now.

Pollution in the channelized stream

Pollution in the channelized stream Mouth of the Ludueña Stream

Mouth of the Ludueña StreamI was surprised to see that, despite the horrible pollution, there were birds, fish and turtles in the stream. The black ones are

biguás (aka

Neotropic Cormorant,

Phalacrocorax brasilianus); I don't know what the other one is. I also saw a group of small birds with pointed wings, black with an iridescent blue patch on the head and back, and a kingfisher (the goddamn bird waited until I was on top of him, camera on hand, and right then it flew away).

Biguás (neotropic cormorants)

Biguás (neotropic cormorants) Some bird

Some bird A biguá up close

A biguá up closeAll of these, of course, were unplanned occurrences.

In the meantime I received an SMS from my friend who couldn't go out — saying he could go out after all. It was dated Saturday at 10:40 PM, about twelve hours before the time when I received it. The cellphone grid works like hell, and I was very angry, but then if I'd gotten out Saturday, I wouldn't have met those birds on Sunday morning.

So I say to my friend, let's go somewhere this afternoon. Sure enough, we meet, get some hot water in a thermos for mate, drop by another friend's house, and head for the Parque de las Colectividades. The streets and the parks near the river were packed.

Parque de las Colectividades

Parque de las ColectividadesLast unplanned occurrence — we run into some friends of my friend and, as the sun goes down, they propose having some snacks. I think beer and peanuts, they think big

picada. No way, I tell them; I don't have that money on me and I just want something light. We settle on a compromise — fried chips (real potato chips fried on the spot, not salty pseudo-potato flakes) and a

carlito (hot sandwich or

tostado with ham, cheese, chicken, red pepper strips, and

salsa golf) with one beer for three of us and water and orange juice for the other two (one had a late hangover, the other one had to drive a car back home). The service was slow, the waitress un-cheerful, the food expensive, but at least it was good enough.

And that's the story of my unplanned weekend.

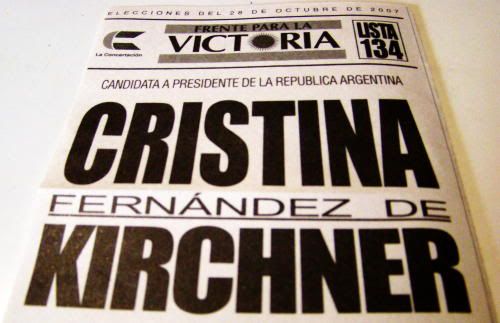

I wanted to write about something that was news only a week ago, and something that wasn't news anymore, though it should be. The former is the

I wanted to write about something that was news only a week ago, and something that wasn't news anymore, though it should be. The former is the

The lecture was fine enough — a brief surview of the relations between Japan and the West, showing how the myth of an enclosed, self-sufficient, almost xenophobic "millenary" culture is just a myth, as many of the things we associate distinctly with Japan were imported or adapted from the Portuguese, the Spaniards, the Dutch, the British or the Americans. The lecturer wandered into another kind of myth herself a couple of times, unnecessarily, for example speaking of the "unconfirmed" etymology of

The lecture was fine enough — a brief surview of the relations between Japan and the West, showing how the myth of an enclosed, self-sufficient, almost xenophobic "millenary" culture is just a myth, as many of the things we associate distinctly with Japan were imported or adapted from the Portuguese, the Spaniards, the Dutch, the British or the Americans. The lecturer wandered into another kind of myth herself a couple of times, unnecessarily, for example speaking of the "unconfirmed" etymology of

The place is called Batten Cottage. There's a string of nice small houses which were built for the VIP of the company, and a group of apartments for the common personnel, both temporary (passing by) and permanent. The apartments still keep their original number plates, and though the place is not exactly crumbling down in slow motion, most of it looks rather 19th-centuryish as well.

The place is called Batten Cottage. There's a string of nice small houses which were built for the VIP of the company, and a group of apartments for the common personnel, both temporary (passing by) and permanent. The apartments still keep their original number plates, and though the place is not exactly crumbling down in slow motion, most of it looks rather 19th-centuryish as well.