You know I often blog about religion, or rather, the bad things of religion in practice — fanaticism, intolerance, and the omnipresent, undue interference of religion in the lives of millions of citizens in Argentina. Every now and then a piece of ridiculous or outrageous news makes me feel I should devote a whole blog to exposing these issues.

Well, that might just happen soon (I need to meditate on a couple of things involved), but in the meantime, I'm opening a section here on D for Disorientation. I'm calling it Religion Watch. Things it won't be about include theology, abstract philosophy of belief, proofs or arguments for or against God's existence, or criticism of some or other aspect of religion. The Watch will be just that: a reaction to those things that every now and then show us the nastier aspects inherent in religion.

Today's post, the first, is about the fuss of the Church at the government-sponsored presentation of a magazine called THC in Chaco. The news article appears in Página/12 and is titled Polémica en Chaco por la presentación de una revista.

THC is, obviously for those familiar with this topic, a publication about marijuana (THC = tetrahydrocannabinol, the main psychoactive substance found in the Cannabis plant). It advocates the legalization of the use of marijuana. It's to be introduced during the Book Fair in Resistencia, the capital of Chaco Province, under the official sponsorship of the Culture Secretariat.

When the Church learned of this, they pounced on the government, requesting that the magazine be banned from the fair, and started spreading rumours that that had indeed happened. Two deputies, one of them the head of the Human Rights Commission, together with Jorge Lestani, the vicar of the cathedral of Resistencia, expounded their bigoted arguments against THC (the magazine, not the substance) and said that the government was going to cancel the presentation. The Sub-Secretary of Culture denied it, saying he would have "nothing to do with any kind of censorship". The vicar replied that "it's not censorship to stop an apology of crime" and that THC's publishers "should be thrown in jail."

This enlightened view was seconded by deputy Ricardo Sánchez, who claimed that THC was trying to infiltrate the cultural circles to promote the consumption of marijuana, and demanded "depuration" and "content control" for the next book fair. In passing he also commented that this (discussing marijuana?) goes against our values, and compared it to the current debates on gay marriage and abortion.

Finally, deputy Marita Barrios explained that "her motherly intuition" had told her that these are actually drug dealers in disguise, and that she and others are doing whatever they can to combat them. She invited society to discuss this grave matter, though from what she said, it seems that "society" is limited to "the community's parents and the evangelical pastors."

These people are full of fear, sick with fear. They fear their small, faith-sanitized world will be invaded by difficult issues where nothing is completely white or black and they might actually have to think hard to distinguish the shades of gray; they consider anything beyond their little circle lacking in taste, dirty, yucky. Their puny worldview would be shattered open if they consented to debating controversial topics such as the legalization of marijuana. You should note they never said: "What this magazine stands for we consider wrong because..." — all they said, all they ever say, is "We don't want to hear about it — we don't want to talk about it — take it away, for God's sake."

Thankfully, they're losing.

29 February 2008

Religion Watch #1: Marijuana

28 February 2008

Powerless

Remember when there was not an energy crisis? Remember when the constant blackouts were not signs of an impending energy collapse but just the growth pains of a flourishing, rapidly expanding economy? Well, we might be heading for another no-crisis again!

Just as they deny that inflation is high and growing, the government is now forcefully denying that the meeting of Argentina, Brazil and Bolivia's heads of state to solve the energy problem was a failure. It was a failure, of course. Bolivia told us they've got contracts signed with Brazil to send 30 million cubic meters per day of natural gas their way, and they intend to fulfill them, unless Brazil agreed to loosen up the terms. Upon Argentina's request, Brazil (that is, Petrobras) kindly replied they're not going to let us have a single molecule of their Bolivian natural gas, because they need it to power the massive (and politically influential) São Paulo's industrial complex. Faced with Argentina's teary-eyed despair, it's quite likely Brazil and Bolivia tried to console her, "You still have Venezuela."

We need fossil fuel for our power plants, industries and vehicles. You can't cut fuel to the power plants, or you'll have blackouts. Angry citizens in the dark aren't good for presidential popularity. You can't cut natural gas for cars, because there are over a million cars in Argentina running on it. You also can't cut NG for homes, because we cook and heat our bathwater with it. You can't cut fuel oil, either, because most heavy vehicles run on it, from the trucks that transport consumer products all across our vast territory to the machines that harvest our crops.

Last year, industries were forced to agree with the government on programmed cuts of the supply of natural gas, and on new working hours. They moved their working shifts around, and to cover the rest of their demand they imported fuel oil from Venezuela at four times the price of natural gas, with some help from government subsidies. This was a problem and will be a problem again this winter, when everybody in the cities starts turning on the NG-powered heaters at full blast. There are some industries and power plants that need natural gas no matter what.

Brazil finally agreed to send a few million megawatts of their spare electricity our way as a compensation for depriving us of our Bolivian natural gas. The offer is neither enough nor well-meaning. It seems Brazil is still angry because last year we re-negotiated the price of natural gas with Bolivia, and Brazil ended up paying a lot more because the new Bolivian government realized they'd been giving it away.

Oh, and Bolivia just realized that they don't have the infrastructure they need to deliver the 20 million m³ of natural gas they'd promised..., the gas for which we're building a huge, expensive gasoduct. We were expecting it for 2010, but Bolivia says the private companies that must invest in exploration and transport of the gas are withholding their money — because they don't like a Socialist/populist government that takes 50% of their massive profits from them. So the gasoduct will be just an empty, useless pipe for a couple of years at least.

Chile also needs natural gas to heat homes. They imported a lot from us, but starting in 2004 we broke our contractual obligations (with some legal protection — national needs are above contracts with foreign companies) and nowadays our gas exports are a trickle (or maybe a whiff?). So not only we're screwed, we're also screwing Chile. Argentina met Chile too, on a separate account, and they agreed that Chilean companies will get natural gas and they'll give our companies fuel oil. This is good for Chile because otherwise they'd have to use diesel, which is pricier. The equation doesn't work for Argentina, however, because fuel oil is so much more expensive than natural gas. Something will have to be done to fix that.

And, of course, this mess is not such, but only the reflection of a flourishing economy. There is and there won't be an energy crisis, and if you say so, you're a conspirator against the government, bent on destroying the country, and probably a neoliberal serial baby killer as well.

27 February 2008

Rain all over

The weather has become unstable as of late, maybe a sign that the tranquil workings of summer's furnace are finally being disturbed by the proximity of the equinox (still more than three weeks away). In simpler terms, it's hot, but it's not sunny and hot all the time — sometimes it's just clammy.

It's softly raining as I write this. Right now I should've been at the Flag Memorial, preparing to watch the reenactment of the first hoisting of the Argentine flag, which took place on the banks of the Paraná River exactly 196 years ago. But it rained cats and dogs right after noon, and then it started again a couple of hours ago, so they called it off, together with other outdoors activities planned for tonight. Of course, the rain did not bring any relief to the heat — it's the same steam-bath as yesterday. With a little more steam.

Like most people I know, I'm a bit sick of this summer. I'm overwhelmed by the heat, the low pressure, the humidity. I don't have the strength to go out and walk and take pictures, or to try resuming outdoors exercise. I spend way too much time sitting before the computer, but I can't think. So I don't have much to tell, and I don't feel like sitting down to write it down, plus I'm having real heavy work at the office. All of this is why I'm blogging intermitently, instead of every day.

The office — that's a real mess. For obvious reasons I can't reveal too much about that here, but let's say conflict is bubbling just below the surface of the provincial administration — the bitter underground conflict between those who want to get to work and finally see there's someone paying attention to their work, and those who have never worked or wanted anything but to suck the state's tit and devote office days to gossip over coffee, and now feel threatened but can't express it openly for fear of being discovered, even though everybody knows what they are. Yes, folks, such are the deep human dramas you find in our public offices.

I intend to wait for more cheerful topics, or at least interesting ones, before I write one more blog post. Let us hope together...

25 February 2008

February, on closing

I've had this impression that February has passed too quickly. True, it's only the 25th, and even though this is a leap year it still has four days to go, but that's mostly done.

This February has been a slow photo month, in large part due to the sun and the heat. I just can't bear doing my picture-seeking rounds in 30+ degree heat with humidity almost visible, least of all when that kind of temperature persists after sunset. (For practical reasons, also, on weekdays I can't stay up and far from home hours after sunset — because the sun goes away at 9 PM and I've got to go to bed at 11 PM to wake up for work the next day.) I guess photographers who don't mind the sauna-like weather, or who can sleep during the day, might be OK with this state of affairs and content themselves with fascinating night pictures of the city. I'm not.

Might it be that February is intrinsically slow? There are no public holidays in February, except Carnival. When I was a little child I remember the beginning of the Carnival season was a huge party — you'd get little water balloons and chase your mates around, or launch the balloons at the girls, and play with your friends and your parents, ideally beside the pool, throwing water around with your garden hose or with buckets. Not only was it funny, it was a public holiday — two days off for everyone, if I remember correctly.

That all seems to have vanished. There are huge Carnival celebrations in some places in Argentina, such as Gualeguaychú, but they're local traditions, not official celebrations. I hear that Buenos Aires City public employees get Carnival days off, but no-one else does. Children are still not going to school, but nowadays when children chase one another in the street, it's commonly with rocks or kitchen knives, and if you throw a water balloon at a random child, you'll probably get beaten by one or both parents, no matter how truly festive your Carnival spirit was.

February also seems to be somewhat deprived of interest to the majority of us who, for whatever reason, see it as a "sandwich month". February is short and stays between the excitement of the New Year, vacations, the fullness of the summer, and the coming of the first cooler spells of March and of the "serious" part of the year — when people start showing less skin, everybody deserts the beach, and children begin wearing school uniforms and filling the early buses. As I said, no holidays, even though February 3 is the anniversary of the Battle of San Lorenzo and February 27 should be the true Flag Day. It seems no-one wants to celebrate in February...

... Except the Rosarigasinos, of course! The photo group decided to gather at the door of the Museum of the City in Parque Independencia to hit the amusement park. The idea, proposed by one of the guys, was doing what he dubbed a "Don Fulgencio Tour", Don Fulgencio being an old comic cartoon character known as "the man who had no childhood". Grown-ups enjoying children's games was definitely a good idea... with some reservations.

First I wanted to try the Ferris Wheel, only to learn that the ride was out of service for some unspecified reason. So we went and rode on the Caterpillar (the local version is known as the Gusano Loco, or Crazy Worm), which was a lot of centrifugal-powered simple fun. I remembered it being my favourite ride when I was a child, and realized I must be getting old when I felt the brief, but cold, bite of fear during the first few turns.

Then some wanted to check out the Mambo. Marisa and I decided that the Gusano had gotten us as much adrenaline as we wanted, so we and a few others stayed while the rest took their place in this round platform that revolved and rocked to the rhythm of cumbia and reggaeton, its passengers facing inward and pressed into their seats by centrifugal force, screaming and clinging frantically to the metal bars, a few heroic photographers trying to snatch pictures of the game from the inside.

Next the children wanted the Bumper Cars. I didn't feel like it; the cars were too many and so there was no room for anybody to bump into anybody as it should be done. Finally, we used our remaining tickets to ride the Loco Bus, a small, slow-moving pendulum ride with one big gondola in the shape of a bus with a cute face painted on the front. Harmless, childish even for an amusement park, good for grown-ups who don't really want so much excitement — so we thought. Wrong! The sensation of falling down backwards while your guts obediently stay behind owing to inertia was powerful enough. The swinging only looked slow from the ground. I got away from it unscathed, but others were not so lucky, and let's leave it at that. All I could say was, thank you thank you thank you for leaving the Ferris wheel out of service!

So this was, in a way, my celebration of February, my Carnival. This week is bound to be gray and rainy, and next Saturday begins March. Let's see what the serious part of the year has in store.

21 February 2008

A museum for our memory

When the international media, or even the national Buenos Aires-based ones, speak of the last military coup and its executors, most actually speak of the junta and its top officials, of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, of the Navy Mechanics School. But of course, the dictatorship took power all throughout Argentina.

Right now several represores are being judged in a high-profile trial in Corrientes. Another group of criminals, the presumed authors of a massacre of prisoners, are to be tried in Trelew, Chubut.

No such trials are in progress in Rosario. Yet here were the headquarters of Second Army Corps, responsible for hundreds of forced disappearances — kidnappings followed by torture and murder, usually. Prisoners were held in a massive building that takes up a whole downtown block. The building was the police headquarters, until in 2001 the provincial government turned it into a local delegation for the southern region of Santa Fe. The municipality of Rosario also got a space. Then an enclosed square was built inside, and after the fire that burned down most of the Natural History Museum, the rest of it was moved to a section of this building as well.

The place where the prisoners were kept is now called Centro Popular de la Memoria. When Boston Review did a coverage of the 30th anniversary of the coup, in 2006, they used one of my pictures to illustrate it... but although the article spoke about illegal detention centers, the main focus was on ESMA, the Navy Mechanics School in Buenos Aires.

Now it seems we'll be recovering another space for the memory of those days. It's a lovely house on a corner, a block away from the CPM, and it's occupied by a bar. The current owners paid a lot for it, and the ones who run the bar would have it forever. It's a prime spot and a beautiful building. But it's also where the orders for the kidnappers and torturers came from.

The place was embargoed, and the municipality paid a sum of money to expropriate it, but the owners would have none of it. Moreover, the ones managing the bar said they had renewed the contract until 2009. The municipality threatened to deny the bar its license, but didn't. And then a judge said the municipality had paid incorrectly — to the federal court that had embargoed the building, instead of to a provincial court.

Days ago, another judge reversed the ruling, so after this ridiculously long legal battle, the bar will have to close and the building will become property of the municipal state, which will install a Museum of Memory there, moving some things (such as photos and documents) from the former site at the CPM. It will open in May 2009.

20 February 2008

Fidel resigns

The news today is, of course, Fidel Castro's resignation, or rather his announcement that he won't seek to retake the power he left in his brother's hands when he got ill two years ago. The headlines are full of Cuba, as are the TV broadcasts.

It's only 8:13 AM and I'm already sick of all the speculation. I've just read some idealized Marxist version of Fidel's ethics and values — "the true human being does not ask on which side life is better, but on which side duty lies" — from a guy who seems to forget that such lovely values lose their meaning if they're imposed on the people by a dictator, no matter how picturesque or how romantic his ideas.

During breakfast I heard a top U.S. government official at CNN explaining that Fidel's evil remains even if he's not in power anymore, so there's no reason to lift the blockade on Cuba, which is intended to deny resources to its Communist regime. With a straight face this guy explained that the Cuban administration is evil because it doesn't let people choose their own authorities and puts people in jail if they don't agree with the government, so it's an enemy of the United States. Hello? China? Pakistan? Saudi Arabia? It seems you have to be small and powerless to be a true enemy of the U.S. You can't possibly be a threat to the U.S. if you're the world's largest exporter of oil, if you have the largest population of cheap labourers and the largest market for commodities, or if you have nuclear bombs. No, it takes a tiny island with a third of the population of California and almost no natural resources to be an enemy to the world's only remaining superpower!

Fidel or not, doesn't anybody realize that if the blockade was lifted Cuba would be inundated with useless capitalist gadgets and trinkets, and that the ensuing consumerist fever would wash away the (apparently very dangerous) ideals of the revolution in less than one generation? I mean, even China came to acknowledge private property! The blockade has been doing a favour to Castro for almost 50 years.

The U.S. should take this chance to flaunt its power, lift the blockade and let Fidel and Raúl Castro deal with it during this, their weakest moment. But doing it would be political suicide. Let's see what happens after the elections...

19 February 2008

Plans for Che Guevara's monument

Last December I wrote about a monument to Ernesto "Che" Guevara. The news now says Che Guevara's monument will be ready and in place in about four months. The place is going to be the same as planned, Parque Yrigoyen, near the old Central Córdoba Station, south of downtown. The date will be June 14, the 80th anniversary of Guevara's birth.

The monument is a four-metre-tall statue depicting el Che in a combative pose, without weapons. It was made from bronze donated by some 14,000 people, often in the form of old keys. The statue will be made in Buenos Aires; a boat will carry it up the Paraná River, departing on May 30 and stopping several times along the way for public events. It will arrive on June 1 or 2, and it'll be installed, I guess, during the intervening fortnight until Guevara's birthday. The unveiling will be attended by people coming on a bus caravan from the Obelisco in BA, some representatives of the Argentine government, and envoys from Cuba.

Rosario, the birthplace of Guevara, has never had anything like this before — not even a museum. There'll be many voices against this monument and all the fuss around it, I know. I'll only repeat what I said in December: Guevara is part of our history and of world history. Ignoring him or refusing to acknowledge his influence would be stupid. Ideological blindness should not lead us to consider him just a revolutionary hero and a fighter for good causes, or just a fanatic and a murderer. The monument will serve everyone to remember that Che Guevara existed and had an effect on his generation, and to make visitors and local residents think about him.

Moreover, the city will profit from this. Tourists are always astonished to hear we have no "Museum of Che Guevara", and often disappointed when they see that Guevara's birth home looks just like any other house and the building is taken over by an insurance company. At least we'll have something to show them now, something big and shiny and three-dimensional that remembers a man no-one can afford to ignore.

Labels: argentine society, che guevara, events, public works, rosario

18 February 2008

Civil unions in Santa Fe... coming soon?

Santa Fe Province is about to join the civilized world, in at least one respect, by passing a law of sex-independent civil unions. You might be familiar with this concept if you live in one of the (still comparatively few) countries that grant special status to couples, no matter whether hetero- or homosexual, who choose to register themselves as such before the state.

In Argentina this matter hasn't been debated seriously, that I know of, on the national level. The Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, the province of Río Negro and the city of Villa Carlos Paz in Córdoba recognize civil unions, each with slightly different implications. A draft for a civil union law was presented to the legislature of Santa Fe, but it was cajoneado — figuratively sent to the bottom of someone's drawer, where it expired without anyone ever caring to debate it. The legislature, especially the provincial Senate, was dominated by conservatives.

The new administration has changed this context quite a bit. It's made up mostly by people who worked in connection to past municipal administrations of Rosario, and their progressive ideas are also supported by a majority of the opposition. The homosexual community has renewed its demands for the recognition of same-sex couples, and now they know they're close to reaching one major goal, with a law project designed by two of their own lawyers, which would give even more comprehensive rights to registered couples (regardless of sex) than those acknowledged by the equivalent law in Buenos Aires City, such as a pension when one's partner dies, and family leave when s/he gets sick. This will hold for all municipal and public employees within the province, in principle, but the project says these are rights that must be acknowledged, as well, by all companies and organizations based in Santa Fe.

The law, they say, should be passed about four months from now, in the political fullness of time, once the debate is done and the paperwork is in place. This is good news not only for homosexuals, but for the many heterosexual couples who won't marry just yet, but feel they're serious enough. The best thing, so far, is that none of that "threat to the institution of marriage" crap that is commonly spread around whenever this discussion is opened, in many countries, hasn't flowed from the pulpits or from behind the desks of bigoted politicians. I'll keep you updated on this.

PS: ... And here comes the first update. A male homosexual couple is going to employ an interesting tactic for effect — they're going to Rosario's Registro Civil (that's where people get married and receive the corresponding papers) at the Center District, and they'll ask to be married. Of course they expect to be rejected, since the Civil Code only recognizes man–woman couples. Once the rejection is formally given, they'll go to the courts to denounce the marriage law as discrimination and ask a judge to suspend its application (this is called recurso de amparo). This is all done ostensibly to bring the issue to media and public attention.

Well, the interesting bit is that, to show their commitment to end discrimination and support the law I mentioned above, the witnesses to the ceremony will be the President of the Provincial Chamber of Deputies, the President of the Deliberative Council of Rosario, plus two other provincial legislators and a national one.

The two guys asking to be married are really a committed couple — a graphic designer and a soon-to-be accountant who've lived together for 5 years. I say this because some may think this is all for show, or merely a private interest group allied with some leftist politicians trying to advertise their "perverted" ideas of same-sex marriage. How can it hurt someone or something to have a couple get their partnership confirmed by the law, I can't conceive, and this is what these guys (people with real faces, with real lives) are trying to show.

PPS: The judge correctly told the wannabe husband-and-husband their thing was a no-no according to the law, before authorities of INADI (the National Institute against Discrimination) and the Sexual Diversity Department of the municipality.

15 February 2008

Out with the old

You may or may not remember Antonio Baseotto, the last bishop of the institution that grouped the military chaplains. Baseotto, an anti-Semitic, pro-dictatorship right-wing fanatic, used to enjoy a juicy wage paid by the State. Argentina not only pays salaries to the Catholic Church hierarchy, but in addition, Baseotto was deemed to have a job of spiritual assistance to the troops. Long story short, he said something he shouldn't and was fired by the Argentine State, but the Vatican refused to acknowledge the dismissal. From that moment on, the relationship between Argentina and the Church deteriorated. The very idea of the Military Vicariate was questioned. It was created during the dictatorship of 1957 through a Concordat (the same kind of treaty that saved the Pope from being expelled from his lands by Mussolini, or the one that preserved the privileges of the Church during Germany's Third Reich). It means discrimination in favour of the Roman Catholic Church. It imposes religion on the troops. It's a financial burden for the state, too.

From that moment on, the relationship between Argentina and the Church deteriorated. The very idea of the Military Vicariate was questioned. It was created during the dictatorship of 1957 through a Concordat (the same kind of treaty that saved the Pope from being expelled from his lands by Mussolini, or the one that preserved the privileges of the Church during Germany's Third Reich). It means discrimination in favour of the Roman Catholic Church. It imposes religion on the troops. It's a financial burden for the state, too.

So these days, Congress is deciding what to do with this link to medieval times, and from the looks of it, it's going to be a big no, even though not everyone agrees. Some say spiritual support is absolutely needed by the troops; some say that's OK but they can go to their regular church if they do need it; others say it's OK to have a chaplain in the war front, but not in peaceful times like these.

What I think is, there's a lot of politics here, but aside from that, a lot of confusion, fostered by religion and by our culture. "Spiritual" doesn't mean "religious". In my experience, very religious people are often less, not more, spiritually advanced than the rest. They cling to their little god and their small-minded prejudices under the guise of dogma, and they don't see the big picture. They have a twisted, one-sided view of the world and of human nature. That's for starters.

Secondly, and this is obvious, having a Roman Catholic chaplain in a country where many people aren't Catholics is discrimination, plain and simple. If a soldier really needs spiritual assistance from a religious "professional", we must suppose he needs someone who shares his same religion. One can hardly expect a Jewish soldier to be consoled by references to a Jesus Christ who welcomes heroic soldiers in the heavens. (If you heard somewhere that Argentina is a Catholic country, now hear this. Most Catholics in Argentina are only nominally so. Catholicism is in retreat. Even the Church acknowledges that most baptized people only go to church once or twice a year, or on special occasions such as weddings.)

Third, you might believe that the State, which puts the soldier in a position where he may be killed for his country at any time, should make sure that he gets spiritual assistance, by paying religious institutions to provide priests, rabbis, or whatever, just as it provides for other needs. This is debatable, but consider it from the other side. Religious institutions who are granted the right to embed their preachers into the Armed Forces, like those who work in prisons and asylums, are given a prime opportunity to evangelize and indoctrinate — they get to the people when they're the most vulnerable, the most permeable to suggestion. Why should we pay religions to indoctrinate our soldiers?

I'd pay if soldiers got real help. But since I don't believe that praying with the troops or sprinkling them with "holy" water is of any value, I won't pay. Let the religious institutions fight for their place, and support themselves. By paying bishops and chaplains, we're in effect supporting the Church with a tithe we didn't sign up for.

It's already preposterous to treat this tiny piece of land inside Rome as if it were a country, worthy of consideration and respect from the rest of the nations. If it weren't for historical and cultural reasons, the Pope would be shunned by the leaders of most civilized nations as what he is — the top of the hierarchy of a theocratic dictatorship, with views ranging from the bizarre to the outright dangerous, and an undue, and bad influence, on pressing world matters (such as the prevention of the spread of AIDS).

The Concordat gives the Vatican some powers that no country has on the soil of other sovereign country, and privileges that no sectarian group should enjoy in a modern society. So I say to Congress, end this ridiculous thing already!

13 February 2008

See No Holy

And now for some good news... The powers that be in Argentina finally seem willing to end the unjustified existence of a shameful institution and, in the process, remind other powers that be that we can't always be treated like fools.

This is most unusual news, one that hasn't exploded onto the headlines but trickled slowly onto less visible places, but by now the matter is like a thick stain.

(You have no idea how difficult it is to write like that. Enough.) Some time ago, former Minister of Justice Alberto Iribarne was proposed as ambassador to the Vatican (or, as they humbly prefer to call themlseves, the Holy See). The normal diplomatic procedure is to let the other country know the name of the ambassador, and ask for its placet, that is, it's official OK. If the other country says nothing for a while, it's understood that they won't OK the proposed candidate, so he or she is silently withdrawn, and replaced in due time with another one, hopefully more acceptable.

Iribarne, so they say, has all the credentials to become an ambassador anywhere... except he's divorced, and currently lives with a woman he isn't married to. The moral censors of the Vatican couldn't let this pass. A man who lives in sin! I mean, you can let child abusers work there, and admit war-mongering murderers like George W. Bush through the gates, but — a man whose sexual union with a woman hasn't been ritually blessed by a Catholic priest? No way.

Yet this wouldn't've become a public issue if it weren't by a mysterious leak to the press. Somebody somehow got the news and published it, and there was a wave of outrage from Argentina, and a counter-wave of supposedly hurt feelings from the Vatican. From our side came support for Iribarne, one of the very few politicians that can be said to have earned the respect of most of his colleagues. Some also noted that, by the Vatican's strict rules, a quarter of all adult Argentine citizens would be considered unfit to talk to the Church as representatives of their country, simply because they didn't repeat the bunch of predigested nonsensical promises that the priest forces couples to utter before the altar.

Adding insult to injury, apparently, the Vatican proposed that Iribarne could be accepted after all, but only if his... how do you call that... let's say female mate... did not ever accompany him in official diplomatic ceremonies. That is, if Iribarne acted like a pious single man, or a widower. Iribarne flatly refused, saying he wouldn't dare impose such indignity on his companion. That's a man, girls.

Argentina isn't going to cut off diplomatic relations with the Vatican — that, sadly, would be unthinkable — but neither is it going to appoint another candidate for the embassy. The post will be left vacant for a couple of years, and a minor official will be left there ad interim. This turns out to be, actually, much ado about nothing, because most diplomatic relations between Argentina and Popeland is conducted through the Papal Nuncio.

What this did serve for was to decide, indirectly, the fate of an institution much younger than the Vatican, much younger than the ludicrous idea that a tiny piece of land with a theocratic dictatorship led by non-elected high priest should be considered, and treated as, a country. I'm speaking of the end of the Military Vicariate. But that's news for another day.

12 February 2008

Bullet trains

This is definitively my comeback, for the time being. Remember you can check out a selection of my vacation pictures on Flickr at Vacaciones 2008. Since Flickr lets you view only your latest 200 photos (unless you pay for a Pro Account), they'll eventually "fall out" of my photostream, but I have them all linked from a private blog, which I'll reveal eventually.

Remember the "bullet train" that the national government is supposedly going to build to join Buenos Aires and Rosario at 250 km/h? Did you see Presidenta CFK defend the project of a second, Buenos Aires–Mar del Plata bullet train? What do you think of it all? A bit over the top, isn't it? More and more it sounds like the stratospheric planes that the Balding Cuckold pulled out of his ass in one of those memorably incoherent speeches of his, back in the 1990s, only this time it looks as if the trains can and will be actually built. (Whether they'll work is another matter.) Although the official version is that everyone's happy about the trains, some are not. I have here an open letter to Cristina K about the trains by writer and journalist Mempo Giardinelli, published in Página/12, and an article about the government's intent to create two state companies to handle the railway system. I've also got an article from La Nación, "Without power, but with bullet trains", and dozens of links to other opinion articles. Now, when Página/12 and La Nación agree that something is horribly wrong, it's usually a sign that it is, indeed, wrong.

Although the official version is that everyone's happy about the trains, some are not. I have here an open letter to Cristina K about the trains by writer and journalist Mempo Giardinelli, published in Página/12, and an article about the government's intent to create two state companies to handle the railway system. I've also got an article from La Nación, "Without power, but with bullet trains", and dozens of links to other opinion articles. Now, when Página/12 and La Nación agree that something is horribly wrong, it's usually a sign that it is, indeed, wrong.

I'll translate parts of what Giardinelli says to la Presidenta after she criticized the press harshly for their comments about the latest train project.

Madam President: Speaking as an Argentine intellectual who lives in the interior of the country, I address you as one among the million of Argentinians who voted for you last October, but also because I was one of the first to doubt, publicly, the construction of the so-called Bullet Train. […] I was one of the first journalists to emphasize the gross contradiction that such a work entails in a country as devastated, railway-wise, as ours.It's difficult to add something to this. Giardinelli, and he makes sure we all know it, voted for Cristina, in large part because he supports the Kirchners' policy on human rights. His letter is all the more valuable for that reason. If Néstor Kirchner hadn't shown his true colours as he ended his second year in office, I'd be agreeing in all respects with Giardinelli. As it is, it's painfully obvious that Cristina is just like her husband — she won't listen to sensible criticism, she'll react with vitriol to any accusations, and she'll stand by her cronies no matter how inefficient or corrupt they might be.

… [I]n a country where railways were destroyed in a vile fashion, and where the transport system is overwhelmed, it makes no sense to execute works that will benefit only a few passengers, the wealthiest of the three largest Argentine cities. In the Spanish AVE trains, for example, the maximum capacity is 329 passengers […] and the Madrid–Sevilla ticket costs between 115 and 174 euro, […] [which] implies a cost of €0.25 per kilometer. At 4.50 pesos per euro, a trip to Rosario (300 km) [from Buenos Aires] will cost AR$324. And to Mar del Plata (400 km) AR$432.

These prices only an elite will be able to afford. And if by any chance they might be lowered, it will be through subsidies, which means we, all Argentinians, will end up paying for the trips of that small privileged elite.

… [T]he original announcement that the Retiro–Rosario bullet train would cost 1.32 billion dollars (some 4 billion pesos) led to the inevitable thought that such a massive amount of money would be invested, with advantage, in the re-enabling of branches […] with renewed railways and better regular [non-high-speed] trains…

… Right now you have announced the Buenos Aires–Mar del Plata bullet train, at a cost of US$600 million, for 300 passengers to travel in little more than 2 hours, at 250 km/h. I ask myself: wouldn't it be more reasonable and cheaper to support air transport, which as of today is in a terminal status, there being barely one or two daily flights to Mar del Plata, when years ago there were tens of them?

Respectfully, Madam, I think you're being wrongly advised. And this is because the head of your Secretariat of Transport is still Mr. Ricardo Jaime, which in my opinion and that of millions of Argentinians is the most inept official to have had a place in the administrations of your husband and your own. His work can be readily appreciated: the collapse of commercial flights, the absurd subsidies to the appalling train services, and the deficient road system that keeps this country from having transversal highways.

As much as, or even more so than the energy crisis, [the issue of] transportation is the heaviest burden on Argentina's development. It is impossible [to conduct] a serious policy of industrialization, full employment and social inclusion in a disconnected country like ours. It is impossible to fight persistent poverty when entire provinces have been and are deprived of railways and airlines, and when their roads are decrepit.

The bullet trains are not, cannot be, anything but the fruit of collusion between government and big business. The exact price of the ticket is not important; the common citizen won't be able to afford it if it's more than twice that of an interurban bus, which is sure to be the case, and that's only a third of what Giardinelli calculated. But the main point is, like he says, that all that money is a waste. It's not a question of wondering whether Argentina can support a comprehensive, well-connected national railway system — this was done before, and it worked fine, but we let it decay and crumble.

11 February 2008

Vacations: Walking with people

I realize I've so far written more about the landscape and the accomodation than about people. That's not right, since I met a lot of very nice people in the way. Marita and Aldo in Junín de los Andes, of course; but also Ana behind the counter in Malargüe's hostel, who got us one more day of stay by juggling with reservations; a certain backpacker and his girlfriend in Lake Huechulafquen, who gave me useful pointers and pleasurable conversation after a whole day of walking alone; a couple of guys from Buenos Aires, another couple of guys from somewhere else; a biologist from Córdoba named Gonzalo who taught me a couple of things about those curious birds I was trying to get pictures of; a girl from Quilmes (Carina) who pushed my lazy ass around in San Martín de los Andes and got me to see the Mirador Arrayán and Chapelco, as well as handing me the pamphlet that led me to my last hostel; Patricia, a girl from Spain, residing in Ireland, who must be still traveling around South America after three months away from home; a guy named Raúl and a girl named Josefina in San Martín de los Andes, who walked with me to Mirador Bandurrias on my last day there; Esteban, a guy from San Lorenzo (a mere 20 km from Rosario) who made and cooked pizza and empanadas from the basic ingredients, just for fun, while in the hostel; and others that I can't remember or whose names I can't recall.

I need to say this, because otherwise I might give the impression that it's OK for me to walk around shooting pictures and do nothing else. But the novelty of marvelous sceneries eventually wears off, and in the end it's often more satisfying to come back to wherever you're staying and have something for dinner while chatting about your adventures with people who may not have been there, and trying to describe what you saw to them, or with others who were there before and don't mind comparing notes, so to speak. Even better if you join others, or get others to join. Conversation for the time being, contacts for the future, at the very least; and the joy of sharing those things you (re)discover when you're on a trip.

I had so much fun during this trip. I also found myself, as they say, a couple of times — and as usual it wasn't a pleasant finding, but one always learns from these.

On Wednesday, January 23, I said goodbye to the people at Ladera Norte, and took a cab to the bus terminal. With me went Esteban ("Esteban the Cook"), who by sheer coincidence had not only bought his return ticket on the same day and the same bus as me, but also on a seat on the same row as mine, and along came Josefina, one of my trekking pals of the previous day, who had to exchange a ticket and wanted to wave us bye-bye in person. We departed San Martín de los Andes at 1:45 PM.

I slept long stretches, stared at the changing landscape, ate cookies, drank water, read and re-read Susan Sontag's On Photography (that Marisa had lent me), chatted with Esteban when we were both awake, got off the bus on every stop to stretch my legs. The trip to Rosario lasted almost 25 hours. When the bus entered my home city, I realised I'd missed it. At the same time, I saw it briefly as it was under the summer sun — large, sprawling, sun-scorched concrete; dirty sidewalks, very green trees; kids on wooden carts pulled by horses, sweaty joggers along the avenues. I stepped down from the bus, spent. It was asphyxiatingly hot, not nearly as hot as it had been while I was away, they told me later. I took a bus home. I felt weak, a bit sick. Maybe it was the heat, humidity, air pressure. I slept and slept, even though I'd slept maybe 16 of the last 24 hours.

I think I came back, truly, a week later.

Labels: 2008 summer vacations, good things, personal, rosario, travel, trip, vacations

10 February 2008

Vacations: Hua Hum

I came to San Martín de los Andes almost by accident. I hadn't included it in my travel schedule, because I thought it was going to be extremely expensive to stay there, as it is in most heavily touristic towns in Patagonia. Well, it is a bit expensive at times. But I was recommended a place to stay and I must say it was the best decision in the whole trip.

The hostel is called Ladera Norte, and faces (precisely) the northern slope of the hills that surround San Martín de los Andes. You need to go up Rivadavia St. on the direction away from the bus terminal.

It was reasonably priced, the service was very good, and the place just opened in last December, so everything from the kitchen to the bathroom sink was brand-new. The best thing was that Santiago, the owner, is a certified tour guide, so he can advise you on all sorts of stuff to do and the best way to do it.

It was Santiago, for example, who told me to go to Hua Hum. After looking at my map, I wanted to visit the nearby lakes; I picked Lake Lolog at random and told him: "I'm going to Lake Lolog — do you know if there's a bus to take me there, and what's the place like?". His reply: "Lake Lolog? Why? That's a shitty lake. You can't go there. You must go to Hua Hum." I obeyed.

Hua Hum is a place on the north of Lake Nonthué, which communicates with Lake Lácar's western end. To the west of Lake Nonthué and Hua Hum is an international pass, and Chile. It's not that close to San Martín de los Andes (2 hours on a bus), but Santiago promised it would be wonderful. It was true.

I arrived and began asking questions, and concluded that my best bet was trekking to the cascade (there's always a cascade!) known as Chachín. The cascade turns into the Chachín River, which empties into the lake, and there are many quiet places along the shores.

If I remember correctly the cascade was said to be about 6 km from the departure point. The way went from a reasonably good dirt road to a steep, winding path full of tree roots and loose stones. It took me about one hour to get there.

(Again one for the newly spawned amateur photographer: if you're trying to photograph a cascade in the sun, forget about getting it all in one shot. You can have the rainbow and the bright surroundings but you can't have the subtleties of colour and contrast and the nice bubbles in the water. Take two pictures. Overexpose the water in one, and underexpose everything but the water in the other one.)

I waited until the rest of the anxious photographers got tired, munching patiently on one of the sandwiches I'd brought with me. Then I did my thing alone, in peace. You can't take a picture while a dozen people are trying to get in the same frame for their friends to take theirs.

I was severely wasted, even after such a short walk. The cumulative effect of sun, dust, wind, hiking, and a macho cold that I'd caught, had made me soft. I took all the time to finish my meal, take pictures, and go back. I lost myself on purpose, took pictures of plants and flowers and insects, and then returned to the path, down toward the river. There I sat myself on the shore, took off my shoes, unpacked another sandwich, and stayed for a while. I'd been feeling not only ill, physically, but also a bit melancholic — but the peace of Hua Hum really healed me.

I had a small problem now — I had to decide what to do with the rest of the day, since the bus would be coming rather late. I had the whole afternoon to myself, but I was still feeling tired, and the only place where I could possibly go was Pucará, a camping site on the southern shore of the lake, 8 km from where I was. Moreover, the road was not a tree-shadowed path across a lovely forest, but a dirt road under the fierce sun. I didn't have that much water with me, and would've rather lain somewhere to sleep.

In the end, all I did was walk around until I found the lake, and then I had coffee and an alfajor at the small inn beside the shore. There was a beach, a real beach with small pebbles and people sunbathing, and a wooden pier in the distance where someone was fishing, and a couple of kayaks in the water. I took out a towel, turned my backpack into a pillow, and half-napped there for an hour or so.

I have this obsession with filling my time with "useful" tasks. Yet lying there, doing absolutely nothing (not even looking around for good photo opportunities), was something I needed and hadn't perceived during all those past days of running around, following tight schedules. I think I slept for short stretches, though I can't be sure. I didn't take advantage of everything Hua Hum has to offer, to be sure, but I did take a lot of peace of mind with me.

All right, so this is not the final installment as I promised... Bear with me just one more day! I still have to tell you about my last day and a half in San Martín de los Andes, where I met nice people and did some more minor exploration, and then finally came back to Rosario.

08 February 2008

Vacations: A preview of San Martín de los Andes

San Martín de los Andes, unlike Junín de los Andes, is what you'd call a small city, rather than a town. It's got a real downtown area, a largish bus terminal, and you can see it coming kilometers away while you're still on the road. It's only 45–50 minutes from Junín, south and a bit west, and closer to the Andes; in fact, the main part of the city is surrounded by cliffs and steep hills on all sides, except on the west, where it drops gently towards Lake Lácar.

San Martín is also rather more touristic than Junín. It has a very, very commercial main street full of wooden-roofed shops that sell camping and trekking gear, ski equipment, souvenirs from the very kitsch carved garden dwarf statuettes to the absurdly expensive silver-ornamented mate sets to the very fine leather jackets, chocolate, more chocolate, and clothing stamped with faux-indigenous patterns and the legends "San Martín de los Andes" and/or "Patagonia Argentina".

In contrast (stark contrast) the city is also a haven for backpackers — come from all places in Argentina but mostly rich kids from Buenos Aires, as well as a number of Chileans, and many Europeans — Spaniards, Germans and Dutch seem to dominate. They don't buy souvenirs, or ski gear, or chocolate. Male individuals tend to be profusely and scruffily bearded. Females are often outsized by their own backpacks (and, thank whoever's in charge, are not bearded). They're gregarious and like open spaces to settle for short spans of time.

You can admire the city from two different miradores (watching spots): Mirador Bandurrias, on the mountains northwest of the city, and Mirador Arrayán, directly south and above the coast of the city. While we were staying in Junín de los Andes, we visited San Martín for the day once. I wanted to see the city from the Mirador Arrayán, but you have to walk about 6 km uphill to reach it and there was no time, so I took a cab.

Yeah, I can cheat sometimes! But I'm going too fast. Rewind to the morning. We arrived, equipped with some tips from fellow travelers, and after some breakfast we went and consulted the Tourist Information Office. As usual, the first thing the tired-looking young lady said was: "Do you have a car?", followed by a tragically disappointed look when we replied "no". We decided to try walking towards the Mirador Bandurrias. As it went, however, we got tired in mid-way, so instead we took a path down the cliff to Playa Catritre, a stony beach on the Lácar. Kids were treading on the cold water, and in several spots people were sunbathing, but even around noon the wind from the lake was blowing rather cool. I took my shoes off and fulfilled my already established rite of wetting my feet in the lake.

A couple of hours and a few sandwiches later, we left Catritre and returned to the city, where Carina, a fellow host at Marita's, met with us at the main square. Carina was leaving soon, so she wanted to see a bit more of San Martín de los Andes: in particular, the Chapelco and the Mirador Arrayán. We took a bus to Chapelco (which is less than hour away), and there went up the mountain using the cable car that is employed for skiers during the season. There wasn't much to see or do there. We took the bus back, and then we went to the Mirador Arrayán (where I took the panoramic picture you can see above).

Besides the Alpine-looking houses and buildings, the other thing that impressed me of San Martín de los Andes was... the roses.

I don't know whether it's by government decree or by tacit agreement among the citizens or a combination of both, but almost every front yard and sidewalk in San Martín is planted with roses, of all the conceivable sizes and colours, some solitary, some in dense bushes. The streets outside of downtown are usually also lined with colourful trees. There are very few places where you feel bounded by asphalt and concrete, as in most of our larger cities.

My next installment will be (I hope) the last one. I'll tell you about the hostel in San Martín de los Andes (a place to recommend) and my visit to beautiful Hua Hum.

07 February 2008

Vacations: A view of Junín de los Andes

As promised, I'll summarize the rest of my vacations in Junín de los Andes, and then on a different post I'll try and do the same with San Martín de los Andes, and be done with it (I kinda want to start writing about local news again!).

After our visit Lake Huechulafquen, the only other thing we did outside Junín was a couple of visits to San Martín. There are buses every other hour that take you there in about 50 minutes. We walked around the city a lot, and I visited Cerro Chapelco and its ski resort (obviously in the low season), but I'll speak of San Martín's main features later.

In Junín we took advantage of the river, which runs only a block and a half from Marita's. There's a little bridge that spans the river and takes you to the banks on the other shore.

The Chimehuin, as expected of Patagonian rivers, is shallow, with a pebbly bottom, very cold, and very fast. I tried to swim in it — but to my dismay I caught a strong current and had to surrender to it, until I was left on a bed of pebbles about 30 meters away.

My embarrassment was compounded by the sight of many children and teenagers who repeatedly jumped into the river, ignoring the certain danger of hitting the bottom, and then proceeded to maneuver easily following the swirls and eddies of the river, and getting (it seemed to me) exactly where they wanted. Needless to say I didn't try swimming again. Of course, these guys were all local people, so they knew the river from long experience; and being young and restless, they weren't afraid of anything.

The other thing we did in Junín was visiting the Via Christi, which is a kind of Via Crucis with sculptures and plaques representing and describing Jesus Christ's path to the place where he was crucified according to the Christian myth.

The other thing we did in Junín was visiting the Via Christi, which is a kind of Via Crucis with sculptures and plaques representing and describing Jesus Christ's path to the place where he was crucified according to the Christian myth.The special thing about this Via Christi is that it combines images and motifs of the Passion with local spirituality, focused on the Blessed Laura Vicuña and the (also recently Blessed) Ceferino Namuncurá, the latter being the first member of a native Argentine tribe to be on the road to Catholic Church-declared sanctity... plus a lot of ecumenical, or syncretic, references to aboriginal spirituality, a vindication of the indigenous tribes, and a retelling of the Spanish Conquest (which didn't reach Patagonia) and the so-called Conquest of the Desert in the late 19th century. The "desert" was Patagonia, which was indeed the frontier of European-Argentine civilization at the time, although it was by no means uninhabited. The Argentine Army, under the command of a typical plutocratic government, advanced over Patagonia and systematically drove away or slaughtered the native tribes it found, or turned the natives into virtual slaves, who were forced into military conscription or sent to work as servants of wealthy families of Buenos Aires; after the land was cleared of its original inhabitants, it was divided in huge fiefdoms and given away to ranchers belonging to the oligarchy who (directly or indirectly) ruled the country.

The Via Christi had elements of this story, as seen from the point of view of modern revisionist history and by recent popular Catholic leaders such as Bishop Jaime de Nevares (1915–1995). I found the whole mix quite funny in its heterogeneity, not because the story was funny in any sense, but because the story of liberation theology is so pathetic — educated folks, with the best of intentions, trying to reconcile modern views about human rights and the struggle of oppressed peoples with the teachings of a church that is fiercely hierarchical and misogynistic, that has supported oppressive governments and countless massacres in the name of its god, and is even today a major obstacle to certain basic human rights in large parts of the world. You have to admire and pity these people for the effort of weaving their version of history into Christian doctrine, even as their own Church stops short of calling them heretics.

The Via Christi had elements of this story, as seen from the point of view of modern revisionist history and by recent popular Catholic leaders such as Bishop Jaime de Nevares (1915–1995). I found the whole mix quite funny in its heterogeneity, not because the story was funny in any sense, but because the story of liberation theology is so pathetic — educated folks, with the best of intentions, trying to reconcile modern views about human rights and the struggle of oppressed peoples with the teachings of a church that is fiercely hierarchical and misogynistic, that has supported oppressive governments and countless massacres in the name of its god, and is even today a major obstacle to certain basic human rights in large parts of the world. You have to admire and pity these people for the effort of weaving their version of history into Christian doctrine, even as their own Church stops short of calling them heretics.The Via Christi also had certain obvious, and to me, rather distasteful hints of anti-abortion propaganda, with abortion compared to the genocide of the natives, and figures looking like small children or late-term fetuses embedded into the beam of Christ's cross.

This funny/creepy tour was very well kept, anyway, and it served as good exercise. When we reached the top of the hill, we could see most of the urban area of Junín de los Andes. The pictures were no good, unfortunately, due to the harsh lighting, but I managed to rescue some.

Our last days in Junín de los Andes were relaxed and festive. We had asado once, and the last night, after spending the afternoon by the river, my friend Gabriel pulled out his finest tricks and made us matambre a la pizza, which is a massive slab of flank steak with cheese and tomate sauce on top, cooked on a grill over charcoal embers (like asado, but not for so long). After that we went out to a noisy bar, and drank just enough to make fools of, but not so much as to endanger, ourselves. No pictures of that, thank you.

Sunday came. Mauro and Gabriel had bought tickets for a direct trip back to Rosario, a bit tired of vacations. I decided to make the most of my time and booked a place in a hostel in San Martín de los Andes. Somehow we woke up after 4 hours of sleep, and after some light breakfast, the guys escorted me to the bus terminal and waited until I left. Their bus departed later that day, at 2 PM — but by that time I was already in my next, and last, destination.

06 February 2008

Vacations: Lake Huechulafquen

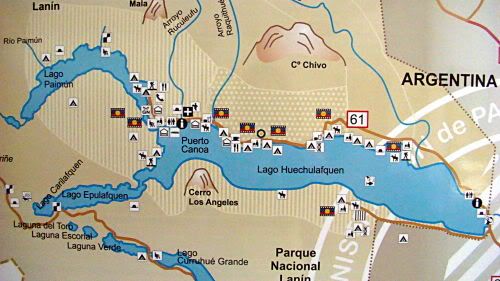

(Resuming the story of my vacations...) The day after we arrived in Junín de los Andes, we took a bus to the northern shore of Lake Huechulafquen, located west of the city, within the Lanín National Park. There are several buses departing from Junín to the place called Puerto Canoa, and back to Junín; we decided to follow Marita's advice and take the first one to go and the last one to return, as there's much to do in this place.

As you go west into the national park, the usually dry Patagonian landscape becomes greener. This is a Valdivian temperate rain forest. Most of this type of forest is located in Chile, but here and there it spills over the passes of the Andes into Argentina. It's noticeably more humid, with tall trees of a variety of species I can't identify, many colourful species of flowers, and moss and lichen growing everywhere.

The other thing you see as you get close to the lake is the ice-clad Lanín, almost 3,800 m high. Sometimes the sight is blocked by mountains and hills nearby, but mostly it's always there in the north, so close you feel you can touch the glaciers near its summit.

(I took dozens of pictures of it from different angles, using different camera settings. Choosing one was a problem — Lanín looks impressive in all of them, with no merit on my part. One thing of note for the photographer, in case you didn't know: when photographing snowy-topped mountains from the distance against the sky, underexpose. Otherwise the pure white of snow and its reflected light will burn off all the details. The picture above is underexposed by one full stop. This may change if you have a polarizer.)

Well, the bus left us a few hundred meters after Puerto Canoa, beside a nice church in an isolated spot of intense beauty. We walked back, marveling at the scenery, until we got to the house of the park rangers. We had to pay a small fee of admittance, and we were given a few instructions and tips. There's a path that takes 4 hours to reach Lanín's base and 3 hours to return, and if you want to go that way you have to notify the park rangers and start before 11 AM; otherwise you can go anywhere as long as you don't violate the rules.

Well, the bus left us a few hundred meters after Puerto Canoa, beside a nice church in an isolated spot of intense beauty. We walked back, marveling at the scenery, until we got to the house of the park rangers. We had to pay a small fee of admittance, and we were given a few instructions and tips. There's a path that takes 4 hours to reach Lanín's base and 3 hours to return, and if you want to go that way you have to notify the park rangers and start before 11 AM; otherwise you can go anywhere as long as you don't violate the rules.There are several camping sites around the lake, which is 30 km long; some have basic facilities including a small "general store"-type shop, while others are more integrated with nature. We heard most of the place was already crowded, and some of the passengers in our bus came to do some camping as well.

We decided to follow a path that would take us to a cascade known as El Saltillo, located some 8 km away north of Lake Paimún, which communicates with Lake Huechulafquen on the west. We began around 11 AM; it took us two and a half hours to cover that distance, the last part being rather steep. The reward for our efforts was spectacular...

After watching the cascade, we came down again and had lunch — some sandwiches. Then we walked back to the lakeshore to enjoy the sight, had some mate, then took a nap in the shade. We didn't have time to try other, longer circuits around the lake, so we walked a few more kilometers and came to rest on a beach, not far from the bus stop. We waited there until it was about time to leave.

It was January 15, only the eighth day of my vacations of two-and-half weeks... so I guess I'd better hurry up before I tire my readers. The following installments will be more summarized, I promise!

05 February 2008

We interrupt this story...

... to bring you the latest news. We'll return to the chronicle of my vacations soon, but in the meantime, a march against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), its largest guerrilla group, took place in Rosario yesterday, February 4. Your host was there, doing some photojournalism at the request of Cristián, a fellow photographer and one of the organizers. I was given a Colombian flag ribbon and balloons of the same colours (yellow, blue, and red).

... to bring you the latest news. We'll return to the chronicle of my vacations soon, but in the meantime, a march against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), its largest guerrilla group, took place in Rosario yesterday, February 4. Your host was there, doing some photojournalism at the request of Cristián, a fellow photographer and one of the organizers. I was given a Colombian flag ribbon and balloons of the same colours (yellow, blue, and red).

The FARC are the de facto rulers of a significant part of Colombian territory, and they've been responsible for thousands of kidnappings and many political assassinations in the last ten years. They're considered terrorists by most of the civilized world, as well as by the United States, though not by Brazil or Venezuela. They're known to fund their activities through illegal drugs and weapons dealing.

The march was one of many organized by grassroots groups in Colombia and throughout the world. In Rosario, it was attended by a small but determined group of Colombian immigrants, their families and friends, and other sympathizers of the cause. It went from Plaza Pringles to Plaza 25 de Mayo along Córdoba St., and finished on the courtyard of the Flag Memorial.

The march was completely peaceful, even when faced with a group of vociferous demonstrators who cheered for "Fidel [Castro], el Che [Guevara], [Hugo] Chávez and Evo [Morales]" and accused U.S. puppet Colombian president Álvaro Uribe of being a "fascist". Uribe tolerates paramilitary groups that are terrorists as much as the FARC, and adheres to the ridiculous "War on Drugs" and "War on Terror" conceptions of the U.S. government and G. W. Bush. For any sensible person who doesn't condone terrorism, of course, this doesn't mean that the FARC are OK just because they oppose Uribe's government and (somehow) Bush's foreign policy — sometimes the enemy of your enemy is not your friend, and sympathy with guerrillas who kidnap, torture and hold people in inhumane conditions for years in the jungle cannot be tolerated. (I'm explaining this simple fact because there are people who seem unable to understand it.)

I took a lot of pictures and a few videos. My girlfriend Marisa took a lot of pictures of her own as well, as did Cristián. * At the end the flags of Argentina and Colombia were flown, and their national anthems were sung. There was a speech and a prayer, and then the demonstrators gave people the rest of the pamphlets they'd brought to inform the public about the march. Marisa and I gave away our balloons to happy children, and went to see the sun go down beside the river.

*Links to my videos (Google Video): Video 1 Video 2 Video 3 Video 4. Marisa's photos: Contra las FARC.Cristián's photos: No más FARC.

04 February 2008

Vacations: Our days in Junín de los Andes

The trip from Neuquén to Junín de los Andes (which you saw in pictures in my last post) took about 6 hours. First we went west, into the arid central plain of the province, where pumpjacks stand solitary here and there, bobbing in slow motion. Then southwest, towards the Andes and the Lake District. We arrived around 2 PM into a little bus terminal with a little wooden information booth beside the platforms. There we asked about La Casa de Aldo y Marita ("Aldo & Marita's House"), our chosen place of stay, and were promptly directed there. There was no need of a taxi, because Marita's is only 6 blocks away, one block from the river.

We arrived around 2 PM into a little bus terminal with a little wooden information booth beside the platforms. There we asked about La Casa de Aldo y Marita ("Aldo & Marita's House"), our chosen place of stay, and were promptly directed there. There was no need of a taxi, because Marita's is only 6 blocks away, one block from the river.

Junín de los Andes lies mostly between National Route 40 and the Chimehuin River, which forms its eastern border. To the west is the Lanín National Park; northwest you have Lake Huechulafquen and, north of it, the volcano that gives the park its name, Lanín, and the Mamuil Malal Pass to Chile.

The city itself is small, a town of about 10,000 residents with a few blocks of well-kept urban features and some commercial activity around a nice main square, plus quiet neighbourhoods of single-story houses and streets that gradually turn to gravel and dirt roads.

Our lodging was a residencial, that is, a kind of hostel that is fashioned out of someone's home. Residenciales tend to be more informal, cheaper, and obviously look more like houses than like hotels.

Our lodging was a residencial, that is, a kind of hostel that is fashioned out of someone's home. Residenciales tend to be more informal, cheaper, and obviously look more like houses than like hotels.Aldo and Marita both run the place, but Marita is clearly the one in charge of the house and its temporary residents, while Aldo organizes fly fishing trips on the river and other aquatic entertainments for tourists, not necessarily the ones in the house. Marita also makes smoked trout and venison, which sell for steep prices in small amounts.

The place, as you'll see from the pictures, can only be described as "cozy" and "warm". You have all the things you can expect from a hostel (kitchen, sink, fridge, some supplies for common use, a common table), and one I hadn't seen before: an asador with parrilla, that is, a special brick oven and a grill to prepare and cook asado, inside the main room. On the other hand, Marita doesn't give you breakfast, but that's not that big a problem. The trouble with Marita's House is the wooden stairs and the upper floor in general. The whole house seems to bend and bow and it creaks loudly as you go upstairs to sleep, and once you're in your bed you can clearly hear everything in the common room. So you'd better be really tired when you go to sleep, or you won't be able to.

We stayed five nights, almost six days in Junín de los Andes, so this is only one of several posts, but I'll tell you from the start that I knew the best part of the trip was about to start as soon as I came into Marita's. People will tell you that Junín simply has too little of everything, but if you go there to rest, you'll find one of the most suitable spots for it; and if you're looking for simple adventure, you'll find it as well.

In practical terms, this whole area and especially Junín de los Andes is suited for budget travelers and backpackers and all others who, like me, don't care for pre-packaged tours. You can find accomodation in dozens of places. Buses come and go, taking you to places where you can experience the majesty of nature firsthand, and back to "civilization", cheaply, safely and quickly. Fellow travelers will engage you in conversation and give you all the best tips and hints. You can choose to walk around, wet your feet in the crystal-clear lakes and quick rivers, climb the hills, or just lie down in the grass. Nature's realm has only recently been invaded by humanity here. True, there are signs and roads, and trash where there shouldn't be, and every now and then a car will come by along the silent road, but that's about it.

Most important for us big-city urban dwellers, who have been increasingly forced to paranoia and mistrust of our fellow citizens, is that this place is one where you can stop looking over your shoulder all the time. You can be sent into a tourist trap by an agency, and you can be scammed, but you can also stay away from that and explore by yourself.

On our first day in Junín de los Andes we just tried to get our bearings — finding out where the center, main square, cybercafés, supermarkets, etc. were. As the sun came down a bit, we hit the square and just lied there with our mate (and my camera). The next day promised to be exciting, our first trip into the real Lake District.

Labels: 2008 summer vacations, hostel, junín de los andes, neuquén, tourism, travel, trip, vacations