Pichincha is located just north and a bit west of the city center, starting by the old railway and port facilities near the Rosario Norte train station. At the beginning of the 20th century, it was a den of prostitution, mafia gangs, police corruption and disease, at a time when Rosario was called "the Argentine Chicago"; a natural consequence of the unchecked growth of a port city overflowing with poor immigrants and uneducated workers moving in from the countryside. Then the port traffic diminished, the country's economy was repeatedly sunk in the successive crises we all know about, and finally the train system was mostly shut down and practically abandoned.

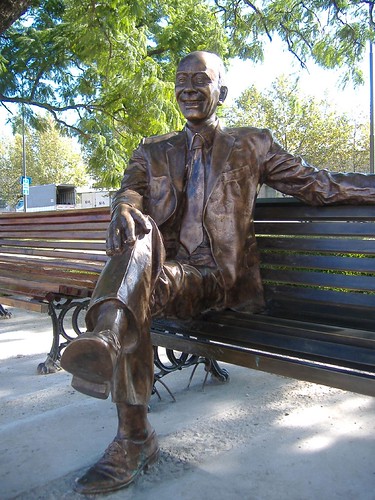

Pichincha has been embellished with nostalgic touches lately; the government of the city and its residents have reclaimed it as a historical district, and life has returned to its streets. This monument to the first and foremost Argentine comedian, quite possibly the most famous Rosarino after Che Guevara, is just the latest touch.

For those who didn't know Alberto Olmedo (which I assume would be most of the foreign readers), he did children's shows first, and then adult-oriented comedy on TV, and he was the pioneer of Argentine sexploitation films. I never really liked the films, and at times I was too little and ingenuous to get Olmedo's adult humour. The man was a master at double entendre and innuendo; he improvised, looked at the camera, told made-up anecdotes about his childhood in Rosario, confused his co-actors and made them laugh at inappropriate times.

For those who didn't know Alberto Olmedo (which I assume would be most of the foreign readers), he did children's shows first, and then adult-oriented comedy on TV, and he was the pioneer of Argentine sexploitation films. I never really liked the films, and at times I was too little and ingenuous to get Olmedo's adult humour. The man was a master at double entendre and innuendo; he improvised, looked at the camera, told made-up anecdotes about his childhood in Rosario, confused his co-actors and made them laugh at inappropriate times.I especially remember three of his characters: the Manosanta (lit. "Holy Hand"), the dictator of Costa Pobre, and Perkins the butler.

The Manosanta was a lascivious "miracle healer" with a headband and spectacles à la John Lennon and a tunic fashioned out of a bathrobe, whose main expertise was fondling his main disciple, a young voluptuous blonde, on the pretext of "imposing hands" on her to "discharge" her negative energies, and then sending her to his room while he dodged the suspicions of her wrathful father.

The dictator of Costa Pobre was the de facto ruler of a banana republic with a name that could be literally translated as "Poor Coast" (the opposite of "Costa Rica"); he wore a ridiculous, pink military uniform and a presidential band with a dedication, "TUS AMIGOS" ("Your Friends") in big block letters.

The dictator of Costa Pobre was the de facto ruler of a banana republic with a name that could be literally translated as "Poor Coast" (the opposite of "Costa Rica"); he wore a ridiculous, pink military uniform and a presidential band with a dedication, "TUS AMIGOS" ("Your Friends") in big block letters.Perkins was a butler working for a wealthy household, where the husband and the wife would be ceremoniously served dinner at the opposite ends of a long table, speaking to each other in formal terms through Perkins. After the master of the house told the butler to send some innocuous message to his wife, Perkins would go to the other end of the table and communicate whatever he pleased to her; by the end of the segment, he had invariably arranged a nighttime visit, supposedly for the husband, to the lady's room — "as always, lights off and no speaking".

El Negro Olmedo is an icon of Rosario, commanding a much more emotional following that the somewhat distantly legendary Che or the largely whitewashed (and sold out) Fito Páez. Some of his old-time friends and early fans still live here. He's also a sort of national hero — not nice, not handsome, not courteous, but a man of his friends, a party animal, a spontaneous laugher, a true Argentinian in the best and worst sense of the word. Ask anyone over 20 and they'll tell you. I just have to have myself pictured sitting next to Olmedo, and I'm sure I won't be the only one.